2020, a good year for generous work incentives? – how the government is really doing

by Gareth Morgan on February 2, 2020

(With a lot of very, very boring but quite important numbers)

This government loves sound bites and bullet points. They can look very impressive.

UK minimum wage to rise by four times rate of inflation

Employees over 25 will receive a 6.2% pay rise equating to £930 a year for full-time worker

National Living Wage increase

Boris Johnson hails ‘dawn of a new era’ as he celebrates Brexit Day with a tax cut

To give workers the feeling of an immediate Brexit bounce, Mr Johnson approved an increase in the threshold at which workers start paying National Insurance from £8,628 to £9,500, resulting in a tax cut of £104 for a typical employee starting in April.

National Insurance threshold increase

BENEFITS BOOST

Boris Johnson will END benefits freeze next year with £5bn welfare hike for 10million Brits

People on Universal Credit and jobseekers’ allowance will see their benefits package increase by 1.7 per cent for the first time in four years.

End of the unprecedented benefits freeze

There’s enough truth in these to justify each claim, and they all seem to add up to an impressive list.

There’s the problem – adding them up.

That’s not how it works. You can’t just add them up, because they all have to work together and that means that adding them together can actually mean taking them away.

I looked at the government’s claim about the generosity of the increase in the National Living Wage (NLW) a couple weeks ago here and demonstrated that for many people the vast majority of the £930 a year goes to the government not the worker. That was based on somebody working for 35 hours a week at the 2020 announced NLW hourly rate and the 2019 tax and National Insurance (NI) rates.

We now know the likely tax and NI rates for 2020/2021 and I thought it might be interesting to look at how much better-off people will be working on the higher NLW rates over a wider range of hours. I want to compare the real gains for people working the same number of hours in 2019, at the 2019 NLW rate, to those working in 2020, at the new rate.

There’s also a lot of pressure to increase the NLW further, so I’ve also looked in less detail at the effect of moving to the London Living Wage which is higher.

That’s why this post has a lot of very, very boring numbers – and a few, I think, interesting conclusions.

I’ve hidden most of the numbers in an appendix at the end of this post, in tables where sad people, like me, who are interested in numbers, can enjoy them and tried to put some of the conclusions in pretty charts earlier on.

So, if you’re sitting comfortably, let’s begin.

“’Tis impossible to be sure of any thing but Death and Taxes”

The Cobbler of Preston – Christopher Bullock (1716)

Governments, of all types, need to pay for their activities, which they do, in the main, by extracting cash from the unwilling citizen. Taxes are the main mechanism they use and, since its temporary introduction in the Napoleonic wars, income tax has been the UK’s tithe on earnings. National Insurance is a more recent tax, intended as a social insurance scheme to pay for health and welfare services but, for our purposes, its effect on earnings is much the same as income tax.

You can earn some money each year without paying any income tax or NI, in 2019 the personal allowance for tax was £12,500 per year (increasing from £11,850 in 2018) and it will be the same from April 2020. The level at which people start paying NI is increasing in April 2020 to £9500 per year; up from £8632 in 2019 (although not to the level that the Prime Minister seemed to promise during the December election).

These levels mean people start seeing money taken from their earnings later and pay less tax and NI. I’m not going to look at higher earners at all in this note. I’m only going to look at lower earners.

People on low earnings, in part-time or full-time jobs, often don’t earn enough to keep themselves and their families adequately provided for. That’s why ‘in-work benefits‘ exist. Whilst it’s unarguable that people should be paid a decent wage, deciding what that wage is and how it should be determined is difficult. Employers base their pay levels on the value of the work done, largely, and not on the needs of their employees. They won’t, generally, pay workers with large families and higher rents more than they pay a single person for doing the same job. They are very unlikely to base their pay levels on the needs of those with the highest living expenses. That’s why governments, of all persuasions, have recognised the need to top up people’s earnings where their needs require it.

In the absence of a basic income or a negative income tax scheme, that means the somewhat peculiar process of different, or sometimes the same, government agencies taking money away from somebody’s earnings and then giving money back to them. That’s where it starts getting complicated.

Means tested benefits are a top up, they look at what the family needs and what the families have got and, if they’ve got less than they need, they pay something to make up the difference. That can often lead to what is called a ‘flat line” problem, where an increase in income is taken away, penny for penny from the top up benefit. The classic example of this, still much in evidence, is Guarantee Pension Credit, the means tested benefit for those over state pension age, where someone who is entitled to a benefit top up on the state pension of, for example, £30 a week, buys an annuity of £25 a week and sees their benefit drop to £5, leaving them with no extra income at all.

For the last decade, governments have been using all their powers to encourage, nudge and penalise people into working more. That’s difficult if every extra pound you earn just reduces your benefits so that you gain no extra income, but probably have extra expenses. That’s why they talk a lot about work incentives.

Work incentives are designed to make sure that you are better off in work and “better-off in work” is the mantra for Universal Credit (UC). The way in which the scheme tries to make sure that people working and claiming UC will gain from working more hours, or earning higher rates, is, unsurprisingly, complex.

Firstly, some people will see some of their earnings ignored, or disregarded, in the calculation; these are called Work Allowances. In the early days of UC, almost everybody had some amount of work allowance but these were severely cut later and now you only get a work allowance if you have children or if you have a ‘limited capability for work’.

From April 2020, the first £512 a month of earnings is ignored but if you’re getting any help with your housing costs as part of your UC then only £292 a month is disregarded. If you’re not somebody with children or an incapacity, then every penny of your net earnings will be taken into account.

The earnings that are used are those after tax and NI have been deducted and also after taking away any money paid into a pension. The effect of this is that the higher tax and NI allowances will increase the money that’s left after they are deducted and thus leave a higher amount of net earnings to be used in the UC calculation.

The second way in which extra earnings are encouraged is by letting the worker keep some of them. For every extra pound, net, which is earned, the UC payment is reduced by 63p, allowing 37p to be kept. That makes increasing your earnings, very different for people on benefit compared to those who aren’t, when looking at the real gains.

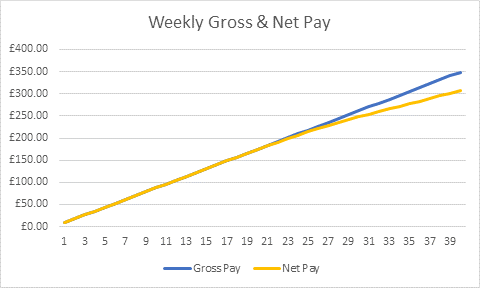

Figure 1

Figure 1 and table 1 show the net pay and gross pay for people working on the 2020 National living wage amount per hour.

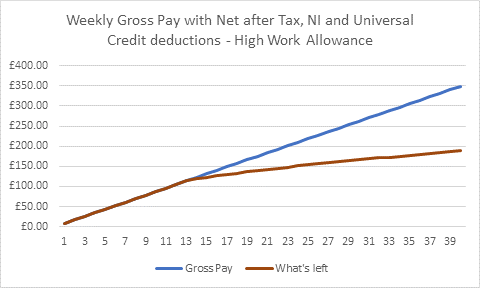

Compare that to the figures for people working the same hours at the same pay but who are receiving Universal Credit.

Figure 2

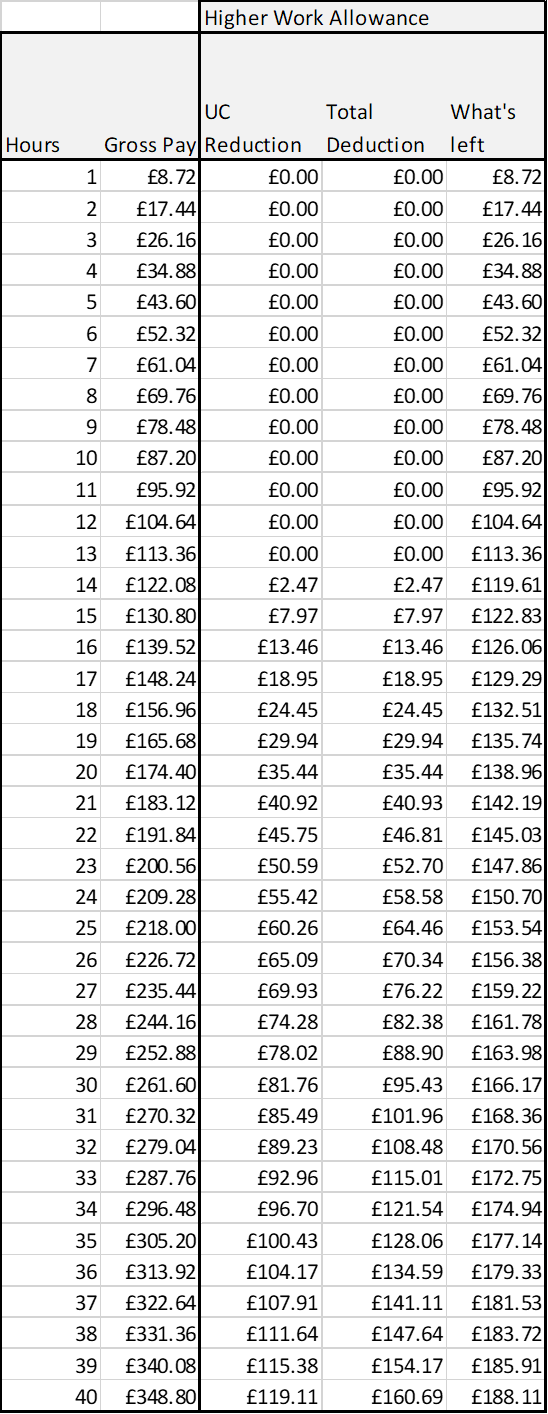

Figure 2 and Table 2 show the gain from employment for somebody receiving Universal Credit and having the higher work allowance. The table in appendix 1 shows the full figures but the chart demonstrates how little real gain there is once the UC deductions begin. Somebody working 25 hours a week at the 2020 NLW rates will be paid £218 gross a week and keep £153.54 of it. Work 30 hours and the gross goes up to £261.60 but the amount kept only goes up to £166.17. Of the £43.60, £12.63 goes to the worker and the rest is taken back by the government in tax, NI and reduced UC.

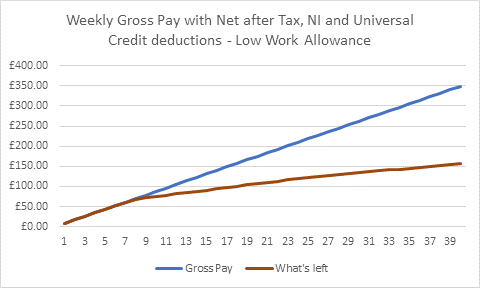

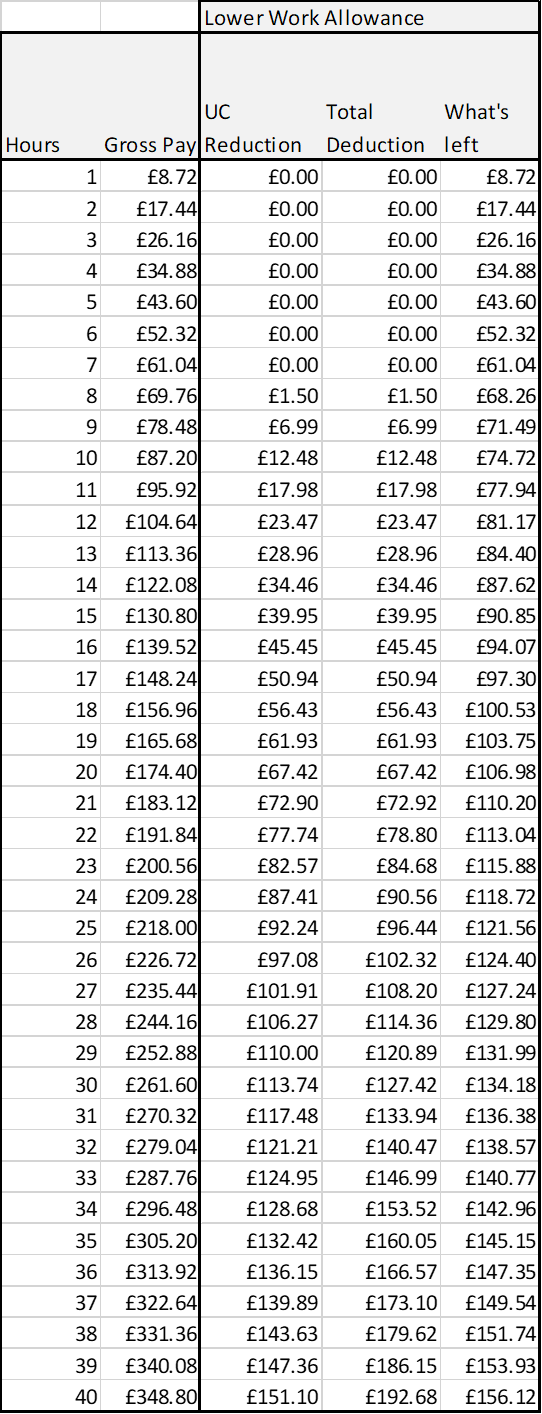

When less is disregarded, as the recipient is on the lower work allowance, because they have housing costs included in their UC, then they keep less of their earnings, as shown in figure 3 and table 3.

Figure 3

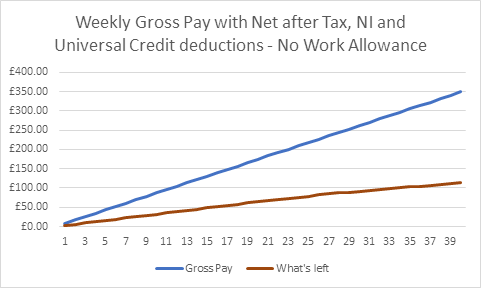

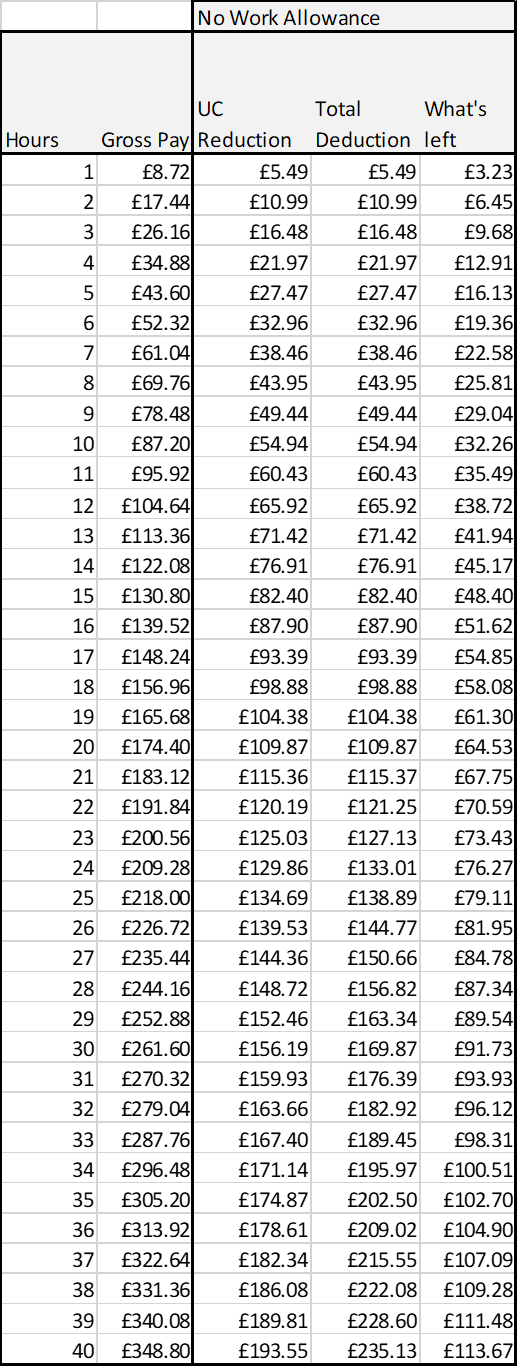

When there is no work allowance, and no disregarded earnings, then less again is left after deductions as in figure 4 and table 4.

Figure 4

If you work harder or longer, and earn more, then you will be better off is the oft repeated philosophy of the last 10 years’ governments. That’s difficult, when the last 10 years have also seen unprecedented cuts in state support. The level of benefits, the introduction of UC and harsh rules on overall benefits levels, the number of children supported, and many other factors have meant that the starting point of benefit support has fallen greatly. It also means that reductions from that starting level of support have greater consequences and incentives less meaning.

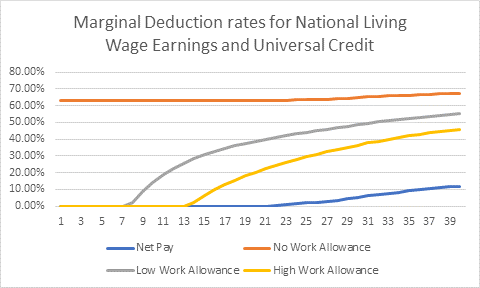

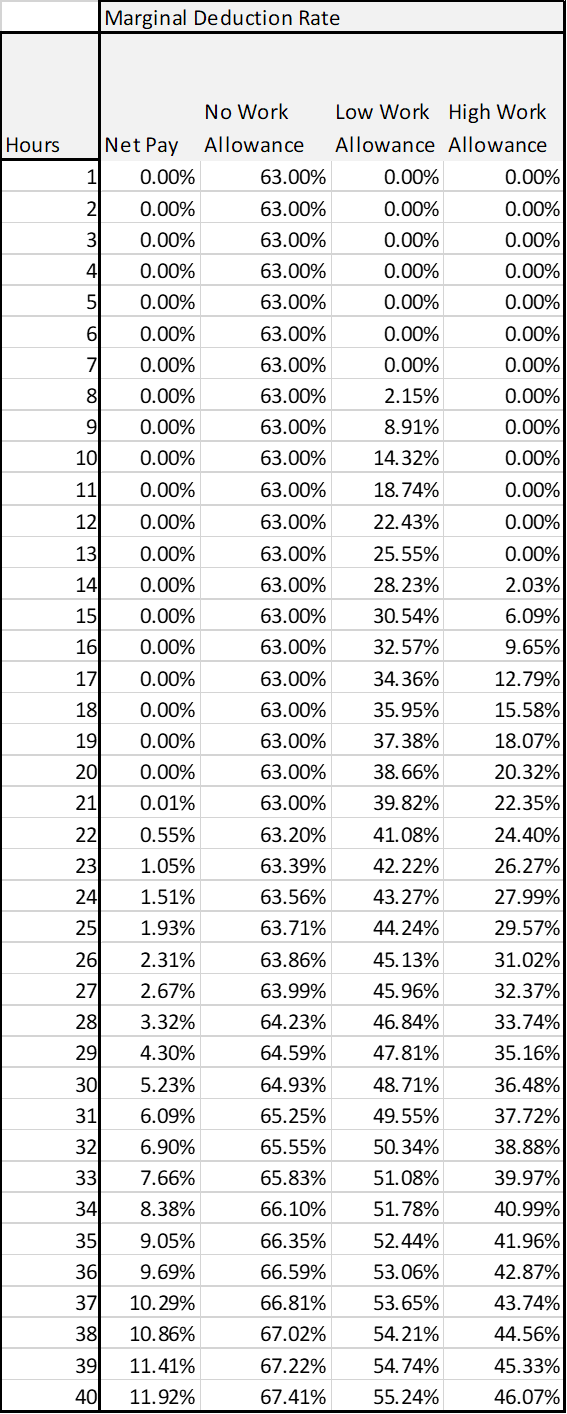

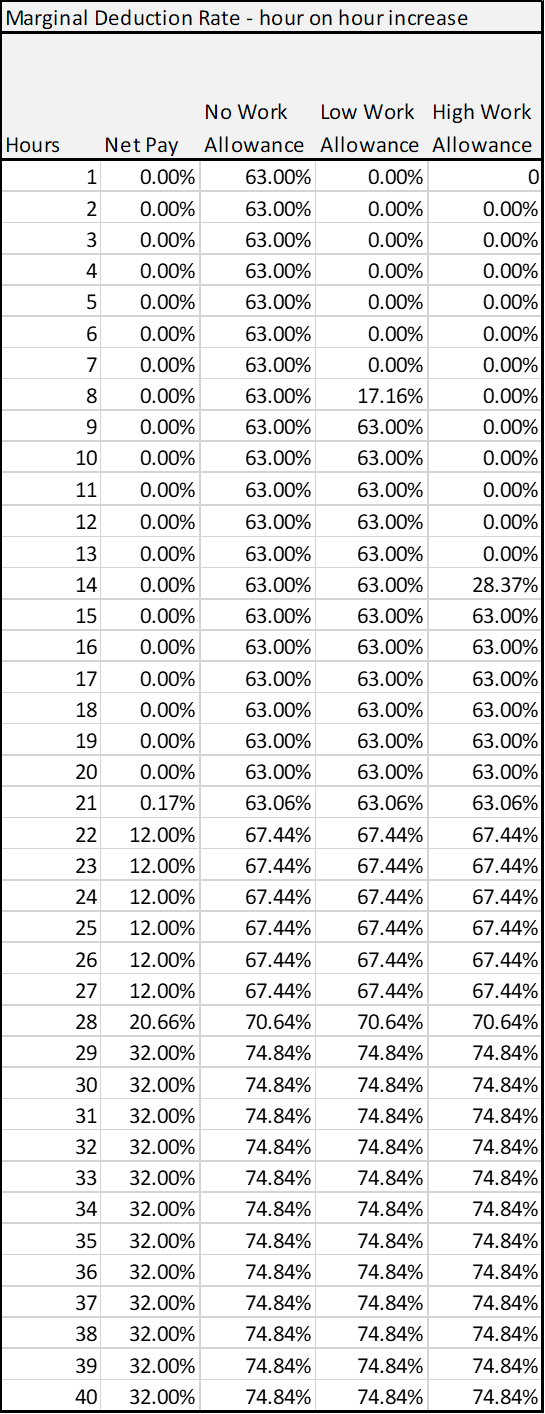

Comparing the total of how much of people’s earnings are taken away by tax, NI and a reduction in UC, called the marginal deduction rate, for the three levels of UC against tax and NI for those on NLW are revealing as figure 5 and table 5 show.

Figure 5

Only those with work allowances, earning below the levels at which tax and NI begin to be paid, will keep all of their extra earnings. Those who are not claiming UC keep a lot more of their earnings and for much longer.

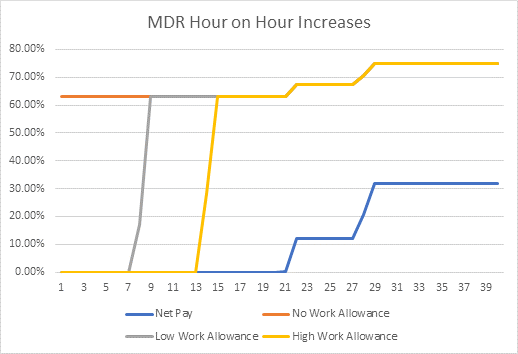

If we look at the deduction rate for each extra hour worked, the incentive to work extra hours can be seen to decrease as hours worked, or earnings, increase.

Figure 6 and Table 8 show the steps in MDR as tax and NI kick in and work Allowances end.

Figure 6

2020 compared to 2019

Is this why the government has made such generous changes in the next financial year? They are very keen to point out their generosity.

-

- a 6.2% pay rise in the National Living Wage equating to £930 a year for full-time worker

- an increase in the threshold at which workers start paying National Insurance from £8,628 to £9,500, resulting in a tax cut of £104 for a typical employee starting in April.

- BENEFITS BOOST – Boris Johnson will END benefits freeze next year with £5bn welfare hike

it’s clear that somebody working the same number of hours for minimum wage in 2020 as in 2019 will be much better off, with a substantial pay rise, cuts in NI and an increase in benefits.

By how much?

Perhaps, not as much as they are told they will be.

The interaction of the elements involved makes the results are less than obvious.

-

- The increase in NLW makes the earnings higher but also can make more of it subject to tax and NI.

- The increase in the level at which NI is charged gives higher net earnings but that can mean more to be deducted from UC.

- The increase in UC rates, the first for four years, is linked to inflation but inflation should have been taken into account for the other areas as well.

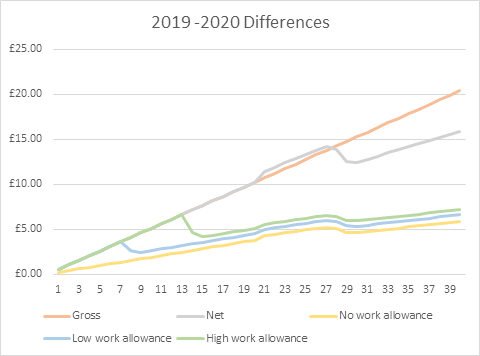

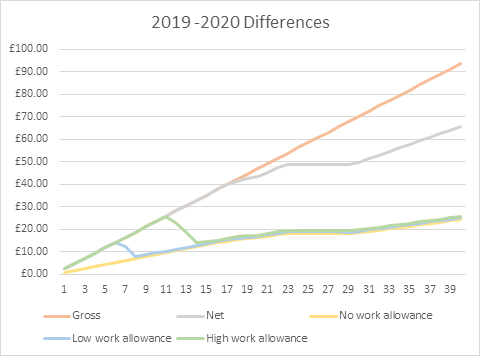

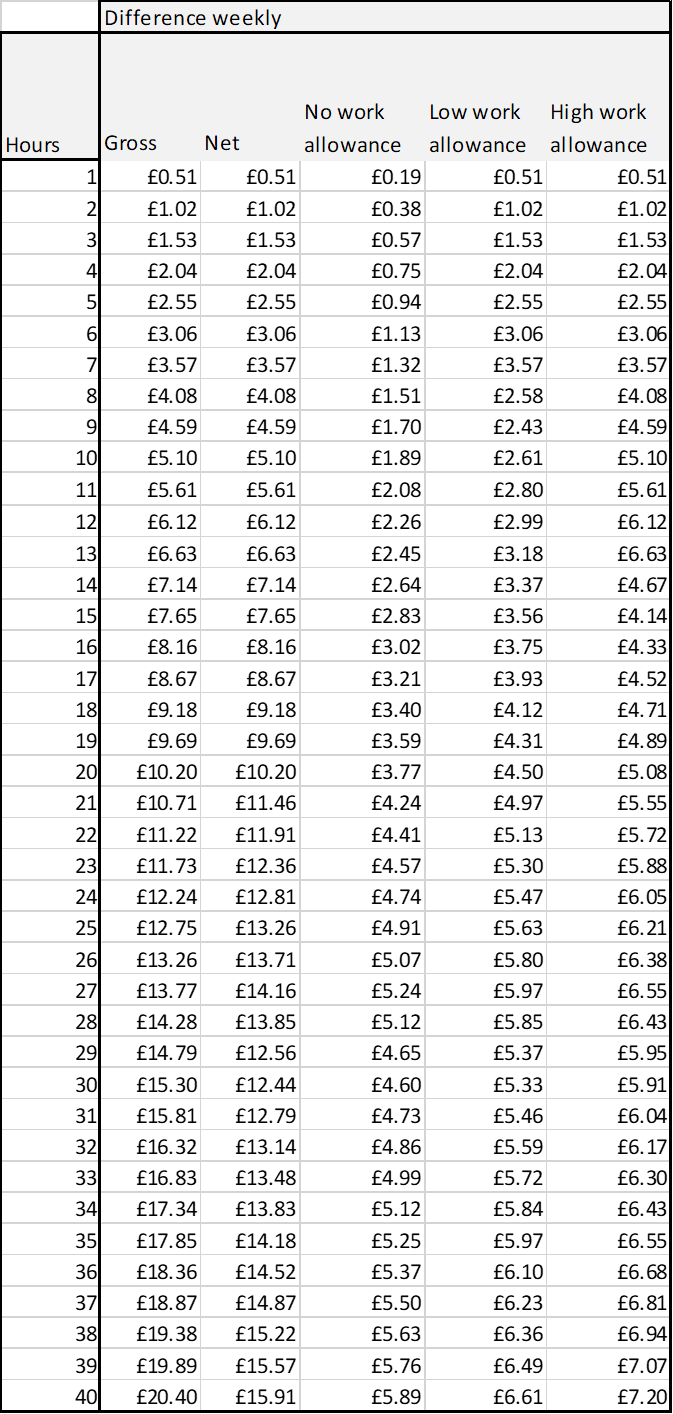

This can be seen clearly (!!) In figure 7 and table 6 showing the weekly differences for each hour of work for each category of comparison

Figure 7

Remember, that this is showing the weekly differences for each hour of work between the 2019 earnings at the NLW hourly rate of £8.21 and the 2020 rate of £8.72. It then takes account of the increase in the NI threshold and the small increase in work allowances.

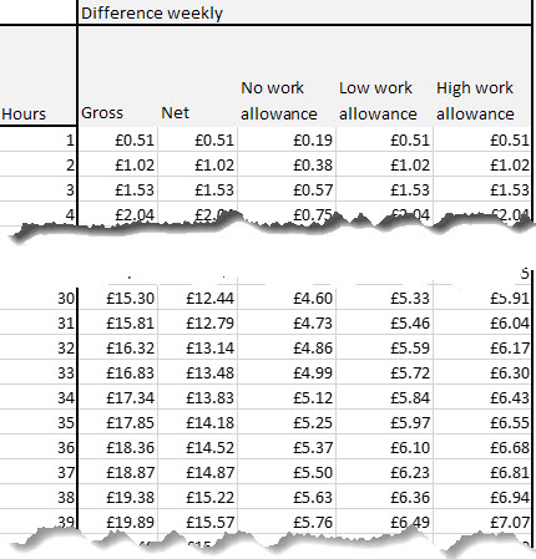

Figure 8 is an extract from table 6 and shows how the differences occur.

Figure 8

You can see that at one hours work the difference between the 2019 gross NLW rate and the 2020 rate has a difference of 51p. As no tax or NI applies the net difference is the same. Similarly, as this amount is below the work allowances figures, then the full amount goes to the claimant. Only where there is no work allowance is there a reduction applied and by taking back 63% of the net increased figure, the claimant is left with 19p more than they would have had for one hours work in 2019.

Comparing 35 hours work, the gross increase is still 51p an hour, giving an increase of £17.85. This level of earnings is above the tax and NI thresholds and we can see that the net effect of having higher earnings, even after the increase in the NI threshold, reduces the gain somewhat to £14.18.

For Universal Credit claimants, without any work allowance, 63% of that is taken away, leaving a net gain of £5.25 a week, £272.82 a year or 15p an hour. For those with work allowances the differences at that level of earnings gives £5.97 extra for those on the lower work allowance and £6.55 extra for those on the higher amount.

No doubt you can see why government also emphasises how simple UC, and its effects, are to understand

“The system will be simpler and will respond more quickly to changes in earnings so that people will not face the same complexities as they do now, particularly at the end of a tax year. As a result people will be much clearer about their entitlements and the beneficial effects of increasing their earnings by taking on more hours or doing some overtime.”

Universal Credit:- welfare that works

Secretary of State for Work and Pensions

November 2010

London Living Wage?

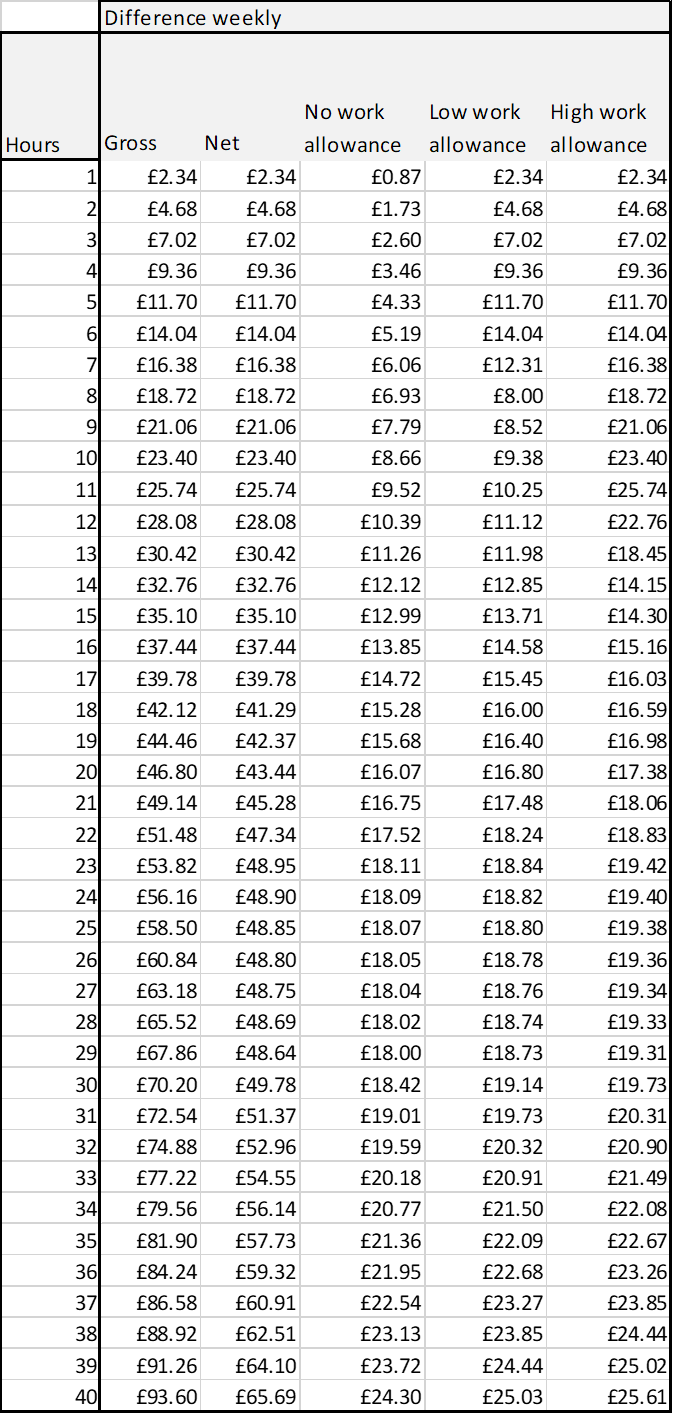

What if the government achieved its ambitions, or responded to the demands of many, and increased the National Living Wage even more substantially? The difference between the 2019 NLW and the London Living Wage, currently £10.55 an hour would be a very great increase. Figure 9 and table 7 show what would happen.

The difference in gross earnings would be over £82 a week for a 35-hour week. For a small number of hours, the resultant differences would be large – five hours work would give the full £11.70 gross difference to those with work allowances, although only £4.33 to those without the disregards. At higher hours the gains would be much less. The £82 a week gross increase for 35 hours work would translate to a gain of £21.36 a week for those without work allowances, £22.09 for the person with a low work allowance and 22.67 for someone with the higher.

Figure 9

Conclusion

There is no doubt that increasing minimum wages does help a lot of people. It can lift them off benefits completely, it may be paid to 2nd earners in a household and, of course, even a small increase in income is worth having.

It doesn’t help if it raises unreal expectations, and that’s what the government presentation of these figures does. It presents the higher gross gains without revealing that there may typically be a 75% deduction applied to them.

More importantly, I suspect that government actually thinks that it is giving people bigger real incentives to do more work than it is – and that might explain why it seems to think that its rich juicy carrots aren’t working well enough and has resorted to the stick.

Gareth Morgan

February 2020

Tables

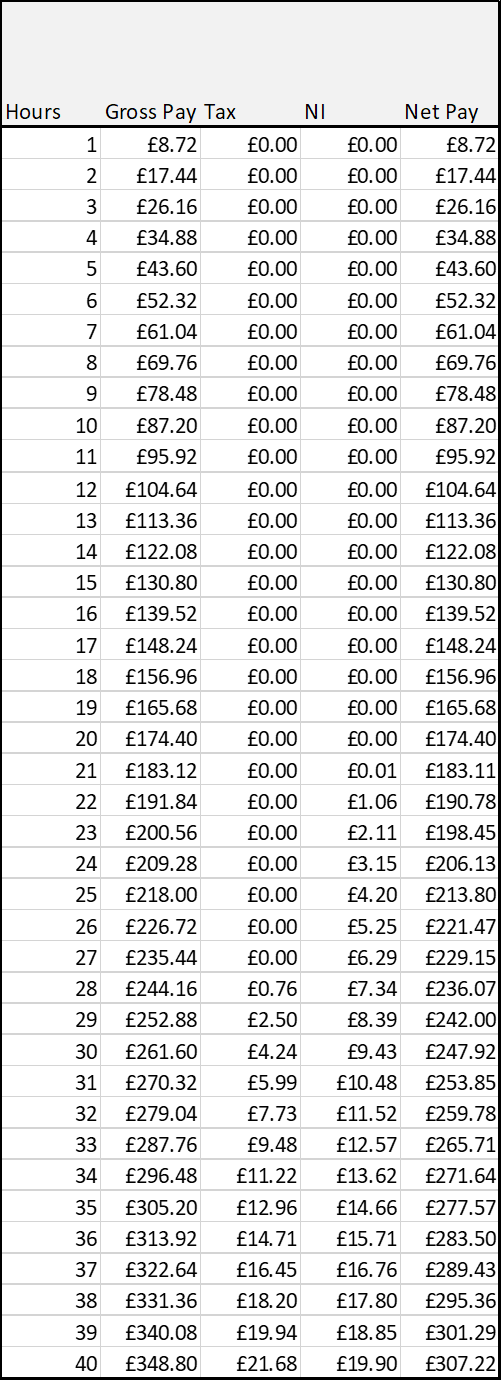

Table 1 Gross to net pay at NLW hours of work 2020

Table 2 Gross pay reduced by tax, NI and Universal Credit taper with high UC work allowance

Table 3 Gross pay reduced by tax, NI and Universal Credit taper with low UC work allowance

Table 4 Gross pay reduced by tax, NI and Universal Credit taper with no UC work allowance

Table 5 MDR at NLW pay per hour

Table 6 – Difference in total gain 2019 to 2020 at NLW earnings

Table 7- Difference in total gain 2019 to 2020 at London Living Wage earnings

Table 8

Comments

[…] 2020, a good year for generous work incentives? – how the government is really doing blog: Excellent and detailed. “I suspect that government actually thinks that it is giving people bigger real incentives to do more work than it is – and that might explain why it seems to think that its rich juicy carrots aren’t working well enough and has resorted to the stick.” […]