5 Years of Pension Freedoms

by Gareth Morgan on June 24, 2021

The House of Commons Work and Pensions Committee is inquiring into the effects of the 2016 changes to the way in which pensions could be used and how to protect pension savers. They have looked at scams already (https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm5801/cmselect/cmworpen/648/64802.htm) and are now, in their 2nd part of the inquiry, looking at the options open to people when they come to access their pensions. In particular they are interested in:

• The options open to people when they come to access their pensions

• The advice and guidance which is available

• The information people need to make an informed choice about retirement products.

They have published 54 written submissions to date, of which 4 refer to state benefits, as far as I could see; none of those coming from the pensions’ industry.

With the committee’s permission, I am posting my submission here, so that any comments can be added.

Ferret Submission to the Work and Pensions Committee Inquiry

Summary

- In this submission I focus on the complexity of the choices facing low-income savers and the extent of the penalty they incur if they make an unwise choice. The issue is about the mechanism by which they access their pension savings, not about the choice of particular products. Examination of examples in considerable detail is needed in order to demonstrate the risks; at the same time the need for this detail underlines the barriers faced by low-income savers if they have no expert assistance and advice.

2. The method of making use of pensions savings is a vital and long-term decision that can often be impossible to change, once made.

3. The effect of pension savings on means-tested benefits can differ, depending on the way in which withdrawal is made. In the submission, I illustrate these effects and how they have changed since the introduction of pension freedoms.

4. The effects can be particularly complex in cases such as mixed-age couples and I consider these.

5. The need for more personalised information about the interaction of pensions and benefits is important, but not readily available and I suggest ways in which this could be addressed, particularly by Pension Wise.

Ferret and Gareth Morgan

6. Ferret Information Systems, founded originally as a Citizens’ Advice Bureau project in 1981, works in the area of welfare benefits, producing advice and assessment systems, training in benefits law and practice and carries out modelling and consultancy in areas of social welfare law.

7. Gareth Morgan focuses on assessing the impacts of changes to the benefits system, in particular, the ways in which the broader tax and benefits systems interact with citizens’ day to day circumstances, their financial decisions and options and the resultant effects. His Blog https://benefitsinthefuture.com/ has been following and commenting on incomes in retirement for many years. He is also chair of Welfare Rights Advisers Cymru, the umbrella body for benefits advisers in Wales and a committee member of the National Association of Welfare Rights Advisers.

Introduction

8. Most of the pensions’ industry, certainly the advisers working within it, appear to have little interest in low-income savers and even less interest in how those with small pension savings make use of them.

9. Personalised advice is expensive and beyond the means of most people, yet it is the only form of advice which actually uses real numbers when considering the circumstances of individuals or families.

10. Even the prevalence of the description of pension savings as ‘wealth’, within the pensions industry, makes it clear to the average person that this is not meant for them. The disproportionate emphasis within the industry on issues such as lifetime saving limits and higher tax reliefs reinforces this situation.

11. This is more than unfortunate, particularly in decumulation, as smaller pension savings often contribute disproportionately to vital day to day needs of older people, and the alternative ways in which they can be accessed may have quite different results in the overall income of these savers, than the same choices have for more prosperous savers.

Before pension freedoms

12. Until the introduction of the pension freedoms in 2015, many low-income pension savers saw little, or no, increase in income from many years, sometimes a lifetime’s, pension contributions.

13. Where their only income in retirement was made up of the state pension and their occupational (DB) or defined contribution (DC) pension savings, they almost inevitably lost a substantial part of both in practice.

14. DC savings, at the levels involved, inevitably had to be used to purchase annuities. These regular incomes, as with occupational pensions, were taken into account in the assessment of any means-tested benefits.

15. In 2015, for example, the full category A full state pension for a single person was £115.95 a week. A couple with a spouse entitled to a category BL pension would get £185.45 a week.

16. The standard minimum guarantee of Pension Credit was £151.20 for a single person and £230.85 for a couple.

17. On those amounts of income solely, the single person, with only the full state pension, would receive Pension Credit of £35.25 a week. The couple would receive Pension Credit of £45.40.

18. A couple receiving two full state pensions, at £231.90, would have £1.05 too much income to receive Pension Credit. They might still have been entitled to other means-tested benefits such as Housing Benefit or Council Tax Reduction, with similar considerations as those described below.

19. A regular payment, whether from an annuity or a DB pension, would be taken into account, in full, in means-tested benefits. In the case of the examples above, the first £35.25 of this income would simply have the effect of reducing the Pension Credit amount payable, by the same amount. For the couple with the lower state pension the first £45.40 of any other pension or annuity would, similarly, bring no actual increase in income.

20. Where the assessed needs, in the means-tested benefit calculation, were higher because of, for example, elements such as disability premiums, then the benefit entitlement would be higher, and the annuity or occupational pension required to generate a real increase in income would be even greater. A similar effect would be seen where there was not an entitlement to a full state pension. Conversely, a higher pension entitlement might reduce the impact.

21. Figures showing the pot size for annuities in Q2 of 2014[1] , before the pension freedoms came into force, showed the mean pot size as £38,400 and the median as £25,600. The annuity which would be received from the pot depends upon personal circumstances, and the provider used, but the ABI in November 2014 said that “a 65-year old buying an annuity with £24,000 from their pension, could receive between £840 and £2,100 a year in income”.

22. Using that as a basis, for each £1,000, an annuity might deliver between £35 and £87.50 a year. The mean pot could provide from £1,344 to £3,360 per annum. The median, from £896 to £2,240.

23. In weekly terms, from £25.84 to £64.61 for the mean pot and from £17.23 to £43.07 for the median.

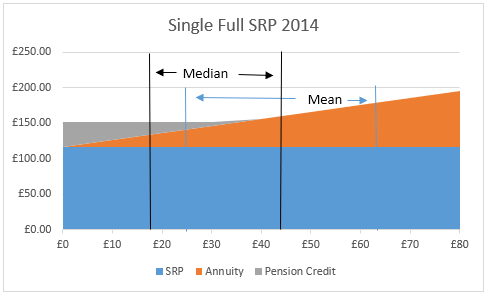

24. Figure 1 shows the effect on overall gross income of these annuity ranges for the single pensioner example.

Figure 1

25. It can be seen that for much of the range of annuities, the effect was merely to reduce Pension Credit and give no real extra income to the recipient. The result is even more clear in figure 2, showing the situation of a couple with one full state pension plus an adult dependant’s addition.

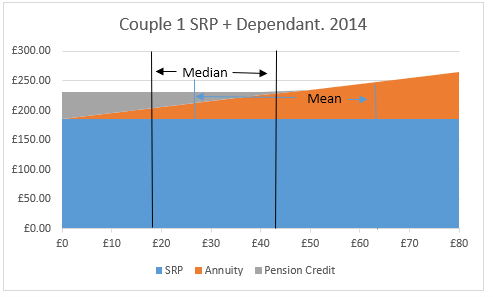

Figure 2

26. In this example, there is no income increase whatsoever across the whole of the median range and little real gain across the mean range, even when Pension Credit has ceased to be paid.

Current situation

27. The pension freedoms have brought something unusual to the world of the benefit claimant – choice. Instead, savers are offered a wide range of products and product types. However, in the vast majority of cases, without any information on how they will be affected by their choice.

28. Although annuities are no longer, effectively, compulsory, large numbers are still taken out. Somewhat surprisingly, the statistics show annuities are still being taken out where people are in receipt of means-tested benefits. It seems unlikely that many of these are being chosen in the full knowledge of the effects they will have on the benefits being received.

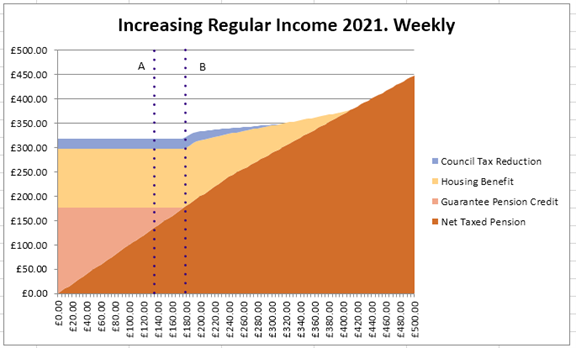

29. Figure 3[2] shows the 2021/2022 situation for a single person over pension age with increasing amounts of net income, from any sources. The top line shows the overall income. In this example, the Pension Credit rules for post-2016 pensioners are used so the calculation does not include Savings Pension Credit. It also models a situation where rent of £120 per week is paid and council tax of £21.15 per week. Not only does this reflect the housing situation of many low-income pensioners but it illustrates the fact that increasing income may have a simultaneous reduction applied across different benefits.

30. It shows that although a full new state pension (line B – £179.60) may, if there are no additional needs, just lift a recipient off Pension Credit, it does not necessarily remove entitlement entirely. Those on the older basic state pension alone (Line A – £60), still retain Pension Credit entitlement. Housing Benefit and Council Tax Reduction entitlement continues, but reduced by the regular pension income.

Figure 3

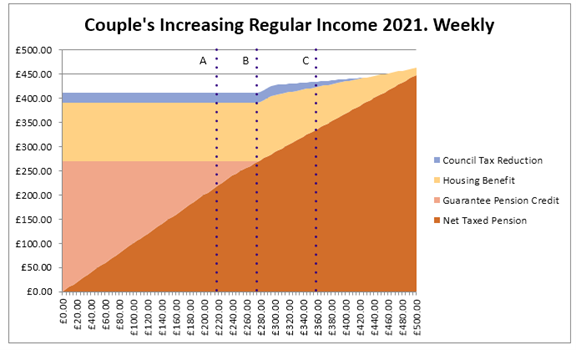

31. Figure 4 shows the same situation for a couple, where line A indicates the income level of a full basic state pension with an adult dependant of £220.05, line B two full basic state pensions of £275.20 and line C two full new state pensions of £359.20.

Figure 4

32. Although no figures are available for the numbers of annuities taken out since pension freedoms, by those in receipt of means-tested benefits, estimates indicate that very many pensioners, or working age partners of pensioners, receiving income from tax credits, Pension Credit, Housing Benefit, Local Council Tax Support, Social Fund payments and Universal Credit are also receiving income from personal or occupational pension schemes – or both. The numbers involved are large, estimates ranging from 800,000 in 2015-16 to 700,000 in 2019-20.

33. While occupational pensions form the largest part of these payments, and are less flexible in usage, many of the personal schemes could be treated very differently if they were used for irregular drawdown of capital instead of regular income.

Regular drawdown

34. Annuities and occupational pensions are treated as income for means-tested benefits, with the effects shown above.

35. Regular drawdown is in a slightly different position when considering the way in which its income is assessed. Unlike the above, there is a retained savings valuation to consider as well. The effect of unused savings has to be considered when looking at both regular and irregular drawdown.

36. The actual capital value of pension savings is ignored in means-tested benefits assessments but, for pension age individuals only, untaken savings also have a notional income value assessed. The calculation for this is based upon the Government Actuaries Department drawdown pension tables and the current 15-year gilt rates from the Financial Times for the previous month at the date of assessment. The amount will vary with the gilt rates and the age of the pension saver but, for a 66-year-old, on May 1st 2021, each £1,000 would generate a notional income of £49 a year or 94p a week. This still falls within the 2014 annuity value range mentioned earlier. It is also less than half of the notional interest rate applied to capital held by Pension Credit recipients as described below.

37. When regular amounts are withdrawn from pension savings then they are treated as being income. The amount of income used in the benefits assessment depends upon the level of the notional income assessed using the GAD tables. Where the actual amount withdrawn is less than the notional income assessed, then the notional income figure is used. Where the amount is greater, the actual amount is used. Figure 5 shows this in an extract from a table of calculations[3]

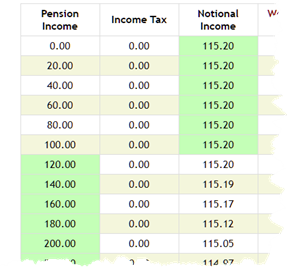

Figure 5

38. The figures shown in green are those that would be used in the means-tested benefits assessment. The value of the pension savings that are untaken, and consequently the notional income value, is normally revalued annually, in practice I am told, taking into account any increases in value and withdrawals.

39. The rules say something different[4] to this practice which, for pension providers could be administratively onerous. It also has implications for the frequent reassessment of benefits entitlement.

40. They specify that there is a duty on the pension provider to reassess the value of savings and to inform the DWP of the changes:

- after every drawdown of capital

- after every drawdown of income which exceeds the applicable notional income amount or

- upon the claimant’s request.

41. The consequences of the revaluation not being carried out each time are clear. The benefits assessment will be using a notional income or capital figure which is too high, meaning that the benefit paid is lower than it should be. The effect can be shown by the slow reduction in notional income shown in the third column of figure 5.

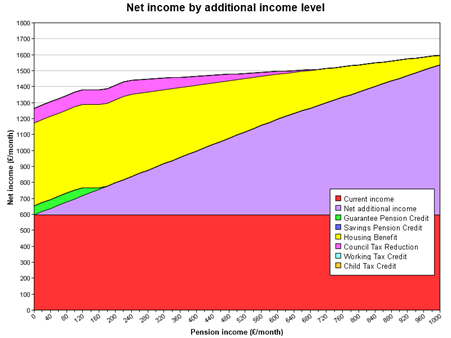

42. This method of assessment can lead to complex results. Figure 6[5] shows the result of increasing the amount of regular withdrawals from the median pension savings pot.

Figure 6

43. The figure shows that the overall income figure in this example rises steeply in line with withdrawals, then flattens before rising again and then continuing to rise slowly. The initial steep rise is misleading. It is actually showing real withdrawals catching up with the notional income that has been applied. In this example, once that figure is reached, the actual withdrawal figure is used, which for a small time merely reduces the Pension Credit payable, until that stops. There is another short period of a steep rise in income before the Housing Benefit and Council Tax Reduction begin to be gradually tapered away.

44. Where no use is being made of pension savings, in practical terms complete deferral, then the full value of the notional income is applied to the Pension Credit assessment.

45. Expecting a pension saver to understand the consequences of taking different amounts of regular withdrawals in this type of situation, without individual advice or guidance is clearly unrealistic. Savers are not notified of the value of the notional income from these savings when they change.

Irregular drawdown

46. Where, however, irregular, or ad hoc, drawdown from pension savings take place, then the withdrawals are treated as capital, rather than income, and another different set of rules apply under the means-tested benefit regulations.

47. Capital rules, which then apply, frequently operate to a substantially different result. For those under state pension age there is an absolute cut-off for means-tested benefits where more than £16,000 of capital is held. Different rules may apply to working age Council Tax Reduction schemes for English local authorities. For those over pension age, there is no capital cut-off for Pension Credit.

48. Some amount of capital is disregarded, having no effect on the calculation of entitlement to means-tested benefits. This is £6000 for working age benefits and £10,000 for Pension Credit. Amounts over the disregard level generate a notional, tariff or deemed, income figure which is used in the assessment. This is £1 a week for every £250, or part, for working age benefits and £1 for every £500 for Pension Credit. These figures, unchanged for many years, may seem to be somewhat ungenerous, using, as they do, notional interest rates of over 20% per annum for working age claims and over 10% per annum for Pension Credit. Such returns are difficult to achieve.

49. Making irregular withdrawals from pension savings may create a situation where the tariff or deemed income could affect benefit entitlement. Where the amount withdrawn is such that the held capital is below the level at which capital generates a notional income, then there is no effect upon the means-tested benefits. This can be illustrated by considering the situation where capital is withdrawn, up to the full amount of savings.

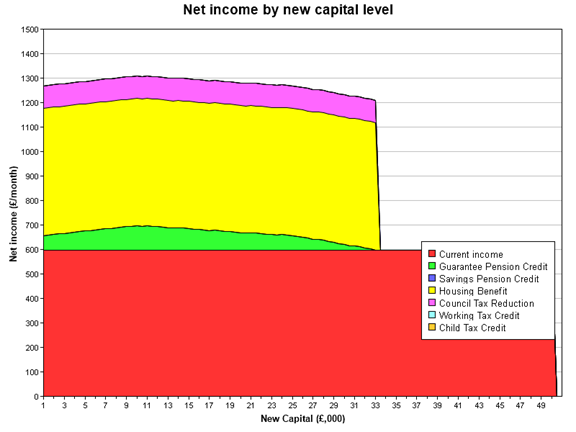

50. Figure 7 shows the effect of withdrawing larger amounts of capital upon benefits entitlement in a monthly basis.

Figure 7

51. The eye is inevitably drawn to the cliff-edge income drop showing passported Housing Benefit and Council Tax Reduction stopping immediately, at the point where Guarantee Pension Credit has been tapered away to zero, by increasing notional income, and the £16,000 capital cut-off for those benefits comes into effect.

52. Look, however, at the beginning of the chart as capital begins to be withdrawn. It shows, initially counter-intuitively, that as more money is withdrawn from the pension savings, benefit actually increases. This effect is demonstrating that, in Pension Credit, the first £10,000 of capital has no effect upon the benefit. The increase is caused by the fact that the reduction in pension savings will cause a reduction in the associated notional income so that the benefit entitlement increases. Once the capital held level reaches £10,000 then the deemed income rules come into effect and the notional income from that calculation exceeds the reduction in the notional income from untaken pension savings.

53. Ensuring that held income does not exceed £10,000 and making ad hoc withdrawals, with no regularity, can be very beneficial in this case.

Working age pensioners

54. The freedom to make use of pension savings from the age of 55 means that increasing numbers of working age means-tested benefit claimants are able to access their pension savings, with many of the same options.

55. Working age benefits have substantially lower personal allowances than those which apply to people above state pension age. The personal allowances within Pension Credit are more than double those on Universal Credit. It is even easier therefore for annuities to wipe out a means-tested benefits entitlement.

56. The effect of capital on those receiving working age benefits is more severe because of the cut-off rules. Capital of over £6,000 has a higher notional income rate while £16,000 held will stop all entitlement.

57. Working age benefits claimants are not treated as being possessed of untaken pensions, even where they have the ability to make use of them. This means that there is no notional pension income calculation applied to the benefit assessment for untaken pension savings.

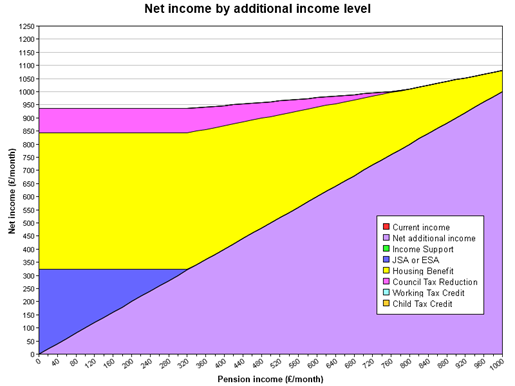

58. Figure 8 shows the effect, on legacy benefits, of increasing regular pensions income. There is no increase in real income until the core means-tested benefit is extinguished, after which Housing Benefit and Council Tax Reduction taper away giving a small real increase in income.

Figure 8

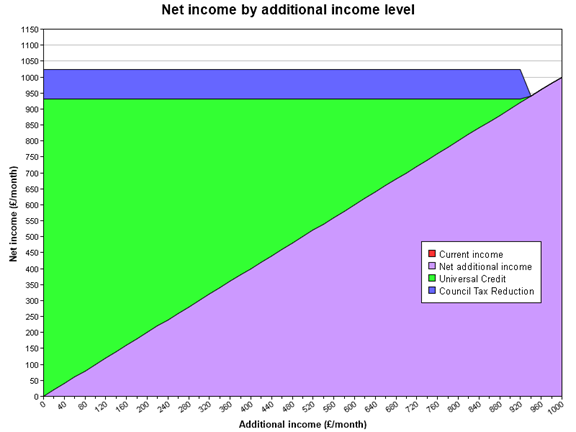

59. For working age Universal Credit cases, with rental support included, the result, in this case, is slightly different as shown in figure 9.

Figure 9

60. Here the flat line, showing no increase in income, is extended, as rental support is also reduced penny for penny and there is a measurable drop in real income when the passported Council Tax Reduction (if it applies in that area) stops.

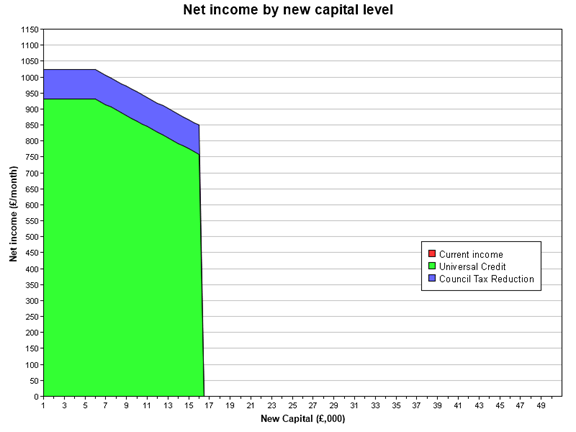

61. Taking pension savings as capital, either in full or as ad hoc irregular withdrawals, produces the results shown in figure 10.

Figure 10

62. Taking lump sums so that held capital exceeds the £16,000 cut off limit will immediately stop benefit entitlement. The first £6000 pounds of capital has no effect, so once again maintaining capital below this figure will not affect benefit entitlement. Because there is no notional income calculation, in the working age means-tested benefit, then there is no, apparent, income increase as withdrawals are made.

63. Taking pension savings, when benefit might be available, will have an inevitable impact on later savings levels.

Mixed-age couples

64. One group facing particularly complex decisions, and situations, about the use of their pension savings are mixed-age couples. These are couples where one member is above state retirement age and one below. Prior to May 2019, couples became entitled to the higher rates of Pension Credit and Pensioners Housing Benefit when the oldest member reached state pension age. Now entitlement only arises when the youngest member reaches that age. Given the sometimes very substantial age differences within couples, it can now take many years before becoming entitled to the much higher rates of older persons means-tested benefits. Pension Credit, for example, has allowances for single people and couples which are more than double the equivalent in Universal Credit.

65. The result is that financial pressures may well cause a couple, in this situation, to feel that they have to make use of their pension savings earlier and more urgently. Even though the assessed needs of the couple will have been substantially reduced by this benefit rule change, the assessment of their resources has not. Any state or occupational pension received by the older member will still be taken into account in full and the notional income from any untaken pension savings of the older member will also be applied in the assessment.

66. Where, as may be typical, earnings have ceased, and the couple’s income substantially reduced, then the pressure to use pension savings may be irresistible. Doing so without a clear understanding of the effect on any benefit entitlement, of their choice of method, could be extremely damaging.

67. In short, the relationship between pensions savings and means-tested benefits is complex, the effects of different choices can be substantial and the numbers affected may be very large.

Advice and Information

68. It is unrealistic to expect savers to be aware of the consequences of their choices of pension use, in the absence of accurate advice or information. Individualised financial advice is locked in the silo of product selection, tax implications and wealth management and largely available only to more prosperous clients.

69. If you have only a state pension, or other low income, and are thinking about what to do with your modest pension savings, then you are unlikely to find holistic advice affordably from the private sector.

70. Financial advisers, questioned by me at conferences and in training sessions, consistently underestimate the levels of income at which means-tested benefits still apply. It is likely that, even where advisers are aware of the potential impact, there is an assumption that benefits will not have any relevance in many cases, where they may actually apply.

71. This is important, albeit for a small number of their clients, as many means-tested benefits are poorly taken-up. Pension Credit, for example, has consistently been unclaimed by about 40% of entitled households.

72. It is clearly particularly important for those unable to afford independent financial advice. Here, there may be substantial numbers of people who make use of their pension savings, in whatever way, while also being entitled to untaken benefits. Their decision to make use of savings, and in what way, might be different if they were in receipt of, or aware of entitlement to, benefits. Informing people about potential benefit entitlement, before they have made choices about savings usage, would provide both a better quality of life and a more informed pension choice.

73. It will be clear that the complexity of the options and choices now open to people, means that they need to understand the consequences of their choices for their individual situation.

74. The practicality of producing the personalised information is not an issue. As has been showing in the generation of the examples in this submission, there are tools available to carry out the pension / benefits / tax holistic calculations necessary for this.

75. The obvious candidate for providing this level of information is Pension Wise, soon to be MoneyHelper.

76. In its 2015 report, the committee recognised the need for them to provide broader and more personalised information:

“Pension Wise guidance is currently too narrow for too many consumers. Decisions about retirement income products are not best made in isolation from information on property wealth, benefit entitlements, tax implications, care costs or debts. We recommend the Government work with the FCA and guidance providers to develop a more holistic Pension Wise service that offers more personalised support.”[6]

77. I would echo much of this but emphasise that this approach can be separated entirely from product selection. It is the type of use that informs the consequences in the first place. Because a wide range of values can be tested for each approach, detailed product figures are not necessary.

78. Pension Wise itself has recognised that there is a demand for this approach.

“This desire for a more personalised service has also been an expressed wish among a small minority of self-serve web customers since this survey began … The service has always been guidance-based rather than offering personalised advice but it is clear that some customers would like it to go further in that direction than the service currently can.”[2]

79. In closing, with apologies for the length of this submission, I would summarise my evidence in the form of recommendations that I hope the committee would consider adopting.

Recommendations

80. Regulated advisers and providers should be required to consider the impact of products on entitlement to means-tested benefits, if in payment.

81. Regulated advisers and providers should be encouraged to facilitate the assessment of means-tested benefits entitlement by customers before they make pension choices.

82. DWP, and other means-tested benefit administrators should provide a regular statement to claimants of notional pension income calculated and used in benefit assessments.

83. Pension Wise should be able to offer integrated individual assessments of benefit entitlement and the impact of different types and ranges of pension usage on the situation of the customer, without consideration of actual products.

Gareth Morgan

May 6th 2021

[1] abi-statistics-q2-2014-the-uk-retirement-income-market-post-budget.pdf

[2] Generated from Ferret’s Future Benefits Model, 2021 edition.

[3] extract from pensionForward pensions and benefits calculator by Ferret

[4] Decision Makers Guide Chapter 28 Para. 28628

[5] This, and following, charts generated by pensionForward – pensions and benefits calculator produced by Ferret

[6] Pension freedom guidance and advice First Report of Session 2015–16, House of Commons

Work and Pensions Committee Para 37

[7] September 2020 Pension Wise service evaluation, September 2020

Comments

Would you be able to help me clarify the following please Gareth…. where a client has a pension pot from which they take irregular drawdowns, is the pension pot itself considered as capital (over and above the £10K disregard) in relation to pension credit award decisions or is it the amount drawn (i.e., that comes into a taxable environment) which is considered as capital? In short, when does a pension pot become capital for the purpose of assessing deemed income for PC claimants? Whatever the answer, are the same rules applicable to council tax reductions?

Pension savings have a unique place in benefits assessments. Anything actually taken from the savings is treated as income taken into account in full. Anything unspent from that becomes capital. Money still in the pot is not treated as capital, as other resources are. Instead a notional income is derived from it, using the GAD tables and 15 year gilt values. This is, effectively, an estimate of what an annuity might deliver. Most CTR schemes work the same way, in theory. I’m less cErtain of thE practical application of the rules.

Thanks Gareth – so is there a distinction to be made for regular drawdowns (prompting notional income) vs irregular drawdowns which seems to prompt ‘deemed income’ i.e., is deemed income different from notional income and, if it is distinct, how does the calculation change and impact on PC?

Not that I’m afraid. Money left in a pot generates notional income, never deemed income. Money taken out, irregularly is capital, regularly is income.

Many thanks for the clarification, Gareth.