Mortgage help, for claimants with earnings, begins again in 2023

by Gareth Morgan on June 21, 2023

Those with long memories may remember the days when the means-tested benefits system offered real help to those with mortgages. Payments to lenders contributed, sometimes generously, to the liability of borrowers for interest payments. There has never been any help towards capital repayments within the benefit system.

Things changed in 2018. Mortgage interest help, as part of somebody’s benefit, stopped. Instead, a system, support for mortgage interest (SMI), was introduced as a loan. The loan has to be repaid, with interest,

- when the property is sold, unless the mortgage is transferred

- if the claimant dies with no household member living in the property

- if ownership of the property changes.

Voluntary repayments can be made at any time with a minimum of £100, or the balance if less.

Taking a loan means that a charge has to be registered at the land registry so that the loan is secured against the equity in the home.

Eligibility for a loan was broadly similar to the previous rules but there were some important differences.

People receiving working age legacy means-tested benefits or Universal Credit had to wait 39 weeks, or nine months, before payments to the lender could start. There was no waiting period for people receiving Guarantee Pension Credit.

No loan was payable to people receiving Universal Credit if they had any earnings at all – the zero earnings rule.

The impact assessments published before the scheme was introduced made some assumptions about the likely effect and acceptability of a loan scheme.

The 2015 impact assessment[1] said

Currently there are 170,000 claimants receiving SMI at a cost to the Exchequer of £265 million per annum. Around 55% of claimants are working age and 45% pension age.

By 2,018/19 the cost of SMI is projected to be £250 million. The number of SMI claimants in that year is projected to be 160,000 (of whom 100,000 – 63% – are working age and 60,000 – 37% – are over pension age.

In 2017, a later impact assessment[2] said

Currently there are an estimated 124,000 claimants receiving SMI at a cost of £205 million per annum (2,017/18)…. The large majority (82%) of mortgage holders are in full time employment. There are currently an estimated 124,000 SMI claimants, with around 48% in receipt of Pension Credit and so of pension age; the remaining 52% of SMI claimants are of working age.

We assume that 5% of eligible working age claimants (those claiming through JSA, ESA or IS) and 8% of eligible pension age claimants will choose not to receive SMI when it is converted to an interest bearing loan (based on an analysis that indicates these are the proportions of each group who have access to funds from other sources, for example beneficiaries or parents). This take up assumption implies that 3,000 working age (5% of 67,000) and 5,000 pension age (8% of 61,000) claimants will choose not to take a loan.

Although the figure is not given in the statement , the forecast for take-up of the loan was 120,000.

In the run-up to the introduction of the loans in April 2018, DWP carried out an exercise to inform claimants about the new system and to assess their likely intentions about the loan[3].

At 21st March 2018, the existing SMI caseload was 90,000 cases.

At 21st March 2018, the changes to SMI have been discussed with 54,000 claimants in telephone conversations. Around 27,000 (51%) have indicated .that they will decline the loan. 14,000 (25%) are undecided on whether or not to accept the offer of the SMI loan, and 13,000 (24%) are intending to accept the loan.

During the run-up to the loan introduction there was a steady and substantial reduction in the number of SMI cases. A House of Commons briefing paper[4] on the new scheme suggested:

This is potentially due to a range of reasons, including changes to the State Pension age and qualifying age for pension credit and fewer pensioners qualifying for pension credit.

An Ipsos Mari report[5] carried out for the department, in August 2017, found :

Among members of the targeted sample of the public, only one in seven (15 per cent) say they are likely to take up an SMI loan, compared with the great majority who say they are unlikely to do this (79 per cent). In contrast, a greater proportion of SMI claimants say they are likely to take an SMI loan (30 per cent), although it is still a minority.

Financial necessity is an important factor in being responsive to the idea of an SMI loan. Among targeted members of the public who are likely to take up such a loan, over half (58 per cent) say it is because they will still need help with mortgage payments, followed by around one in five (21 per cent) who say they have no other option.

Among SMI claimants likely to take up an SMI loan, over half also say it is because they will still need help with their mortgage (52 per cent) and they are even more likely than members of the public to say they have no other choice (36 per cent).

The actual figure for take-up has been much less than forecast. The take-up of loans at the beginning of the scheme was 6,897 which has gradually increased, from the latest figures for May 2022, to 12,845 loans in payment. The total number of loans which have been made is 23,764.

A March 2022 report by DWP, ‘Support for Mortgage Interest Loans: Take-up’[6], provided a very useful update on attitudes to the loan and the likelihood of take-up. It sampled eligible individuals who had not taken the loan.

Those that are in more financial difficulty, who represent approximately 20% of all eligible non-recipients (i.e. those who were eligible for a SMI loan, but who declined the opportunity), are more likely to say they would take one out in future. Just over half of all respondents (52%) say they are not at all likely to take an SMI loan in the future, and overall close to three quarters say they would be unlikely to do so (72%).

Mortgage lenders, according to the report, believe that the change to a loan has better targeted those in real need of support.

Their view was that previously many SMI benefit recipients were in receipt of Pension Credit, and viewed the SMI benefit as a ‘nice to have’ Take-up of Support for Mortgage Interest Loan rather than a necessity, whereas current SMI loan claimants are in real financial need, and genuinely struggling to cover their mortgage payments.

In the executive summary, the report says

The main reasons for being unlikely to take up an SMI loan relate to an unwillingnessto take out a loan, and a reluctance to add an additional charge to the property,although, reflecting the qualitative findings above, one in five report being able toafford their mortgage payments without the SMI loan.

Four in five respondents say their source of payment has not changed over the pasttwo years, and a similar proportion agree that they will be able to continue to use thismethod to pay their mortgage for the next year, including half who strongly agree,suggesting repayment methods are perceived as sustainable by the majority ofrespondents.

However, while three in five agree, a third disagree that they would still be able tomake their mortgage repayments if they suddenly experienced an unexpectedsignificant expense, suggesting that this sustainability is fragile for some.

The fieldwork for this report was carried out in August 2020 when, even though the covid pandemic was in effect, a five-year fixed mortgage was typically 2.49%. At the time of writing in June 2023 this rate has risen, on average, to 5.67% which might be expected to count as an unexpected significant expense.

The largest number of loans to means tested benefits recipients has been to those claiming Employment and Support Allowance. This was not expected, although the impact on disabled people was noted in the 2017 impact assessment

Over one third (38%) of SMI recipients are claiming ESA (38%) and almost half (48%) are claiming Pension Credit (48%). Claimants of these benefits are more likely to be affected by some form of disability than the population in general. Based on self-reported data on disability status according to the Equalities Act 2010 definition, in the proxy group for SMI claimants 74 per cent of single claimants are disabled and 80 per cent of couple claimants have one or more member that is disabled. In comparison, 17 per cent of all single mortgagors have a disability and 21 per cent of couples with mortgages have a member with a disability. This indicates the policy is likely to have a disproportionate impact on disabled people.

The current proportions show very nearly 50% of loans in payment going to ESA claimants and 21% going to those claiming Pension Credit. 19% of loans are made to those claiming Universal Credit currently but the zero earnings rule means that these are made to those where there is no adult working.

The Universal Credit figures will change in 2023 with the abolition of the zero earnings rule. The previous nine month wait for working age benefit claimants has also reduced to 3 months from April 2023.

Should people, who could now get a loan, take one?

The experience of the past five years suggests that only a small minority of those who qualify for a loan will choose to take one. Is that a wise choice?

There are a number of factors which will determine the cost of a loan and its comparison to the situation of rejecting one.

The long term costs of a loan are impossible to identify precisely, without a crystal ball. There are a number of factors which may change during the term of any loan. The rate of interest being charged, the rate determining the payment to the lender, the mortgage rate of the current scheme and, for a number of reasons, the rate of house price inflation or reduction.

This does not mean that it is impossible to provide some useful information to help people to decide whether a loan could be appropriate or not. Ferret have produced a reckoner[7] which can be used to compare the options but based on assumptions. It’s designed to allow the user to quickly test the effects of changes in these factors by showing the results of the changes.

Before taking the loan people should receive independent financial advice but information about the possible consequences of taking a loan can be given by other advisers. This is where the Ferret reckoner could prove useful.

The following examples use the average figures from the March 2022 report for mortgage loans, of £62,633 and monthly payments made to the lender of £342. A low house value of £100,000 has been used in the modelling as a basis for considering equity and the comparisons of mortgage rates use the five year fixed mortgage rate in December 2020 of 2% and December 2022 of 5.67%. The same values are used throughout for comparison purposes. The current rate of loan contribution paid to the lender is 2.09% but between April 2018 and April 2021 it was 2.61%. The current interest rate charged on the loan is 3.03%, increased in January 2023 from the previous 1.40%. This figure is set by the OBR gilt forecasts and can change twice a year., as described later.

At a time of high inflation and frequent substantial changes to interest rates, the values used within the SMI calculation can also be expected to change substantially. This may be expected to have a large effect for some using the SMI loans.

On the contribution paid to the mortgage lender for the £62,633 average loan figure, the lender would have received £109.09 a month.

On the interest paid on the £62,633 average loan figure, assuming the 2.09% lender payment remains the same, the loan interest each month would be 1.4% of £109.09 divided by 12 – or £0.12727 a month while in January they would pay £0.27545. But it must be remembered that interest is applied each month on the total of the previous loan payments and interest liability compounded.

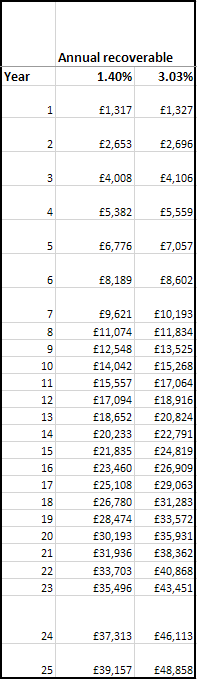

Table 1 shows the effect of this compounding on the amount of loan recoverable. initially the difference is small but as the loan is held for longer, the difference becomes much larger.

Table 1

It must be remembered that this is, effectively, replacing the mortgage interest payable on the same amount. it is very likely that this would have been larger, if the equivalent interest was not being paid and instead accrued.

Should people take the loan?

That isn’t for me to comment on , I’m not a regulated financial adviser (this is not financial advice), and there will of course be a large number of different factors which can affect people’s decisions. There are however a few objective features that are worth looking at.

If someone is able to make all of the mortgage payments on time with their own resources, there would seem to be little argument in favour of taking the loan, paying the loan back immediately , avoiding any long-term compounding of interest payment , might be seen to be adding unnecessary additional complexity , where it could otherwise be incorporated into the payment to the lender .

If the mortgage is interest only then, at the end of the term, repayment of the capital will be on the same terms as when the mortgage was taken out . The mortgage loan is always unconnected to any capital issue.

In the modelling of these examples, it must be remembered that mortgage rates applicable to individuals will be very varied. Those on low long term fixed rates will be in a very different situation to those people having to take out or renew a mortgage loan following the recent financial turmoil. There will also be those who, because of personal circumstances, will find themselves with extremely high rates. For simplicity in these examples, we will use a rate of 5%.

A mortgage of £62,633 at an interest rate of 5% would require a monthly payment of £260.97. After any waiting period the mortgage interest loan, at 2.09%, would be £109.09. That would still require a payment by the borrower of £151.89.

That payments together with the loan would meet the interest requirements leaving the equity in future (assuming no house price inflation) and changed and the capital repayment requirements also changed.

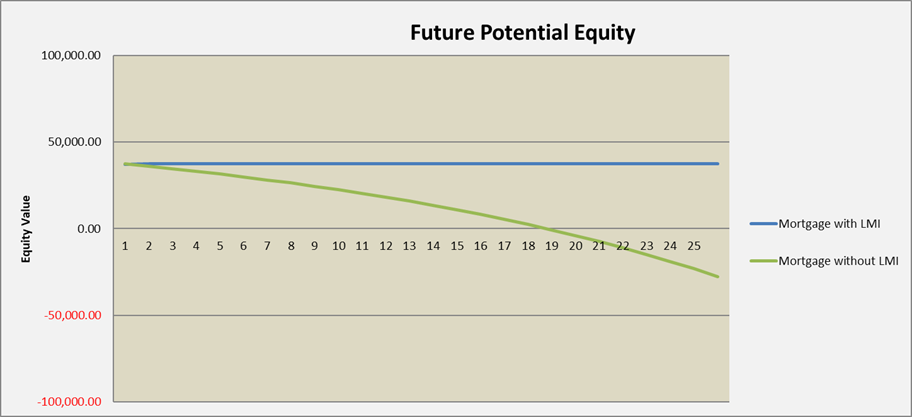

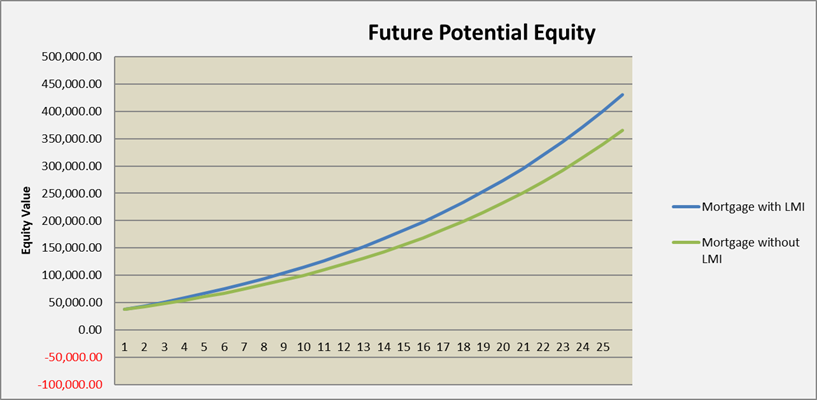

If, without the support loan, the borrower were only able to make payment of £151.89 a month, then a comparison, assuming the lender took no action on the shortfall, would be shown in figure 1.

if the borrower is only able to make the mortgage interest payments due by making use of the loan the situation is quite different.

In the case of interest only loans.

Figure 1

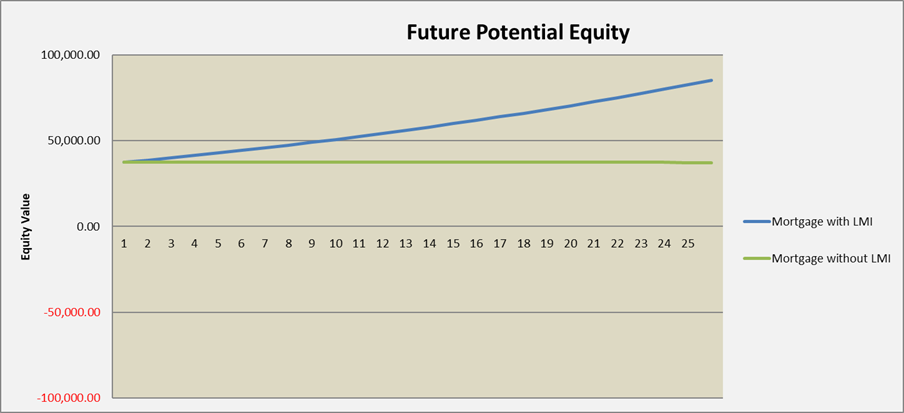

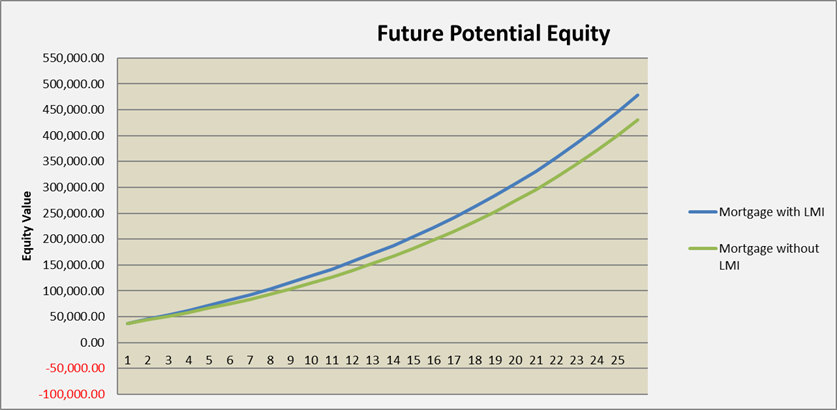

If the borrower however was able, and continued, to make the monthly payment of the full interest amount of £260.97, and the LMI became an additional payment to the lender, then the future equity would look very different.

Figure 2

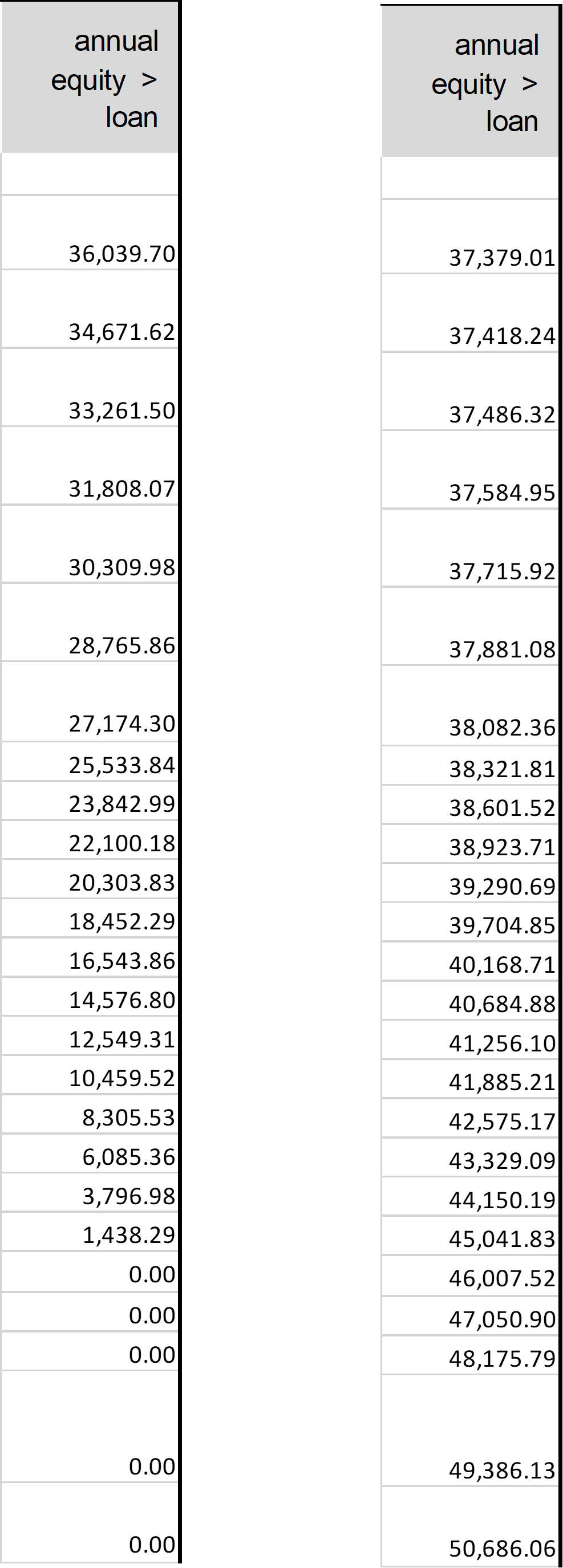

In both of these cases, there would be a repayment requirement, as shown in table 2.

Paying less Paying more

Table 2

Where the whole interest is being met from the customer’s resources then the capital payable at the end of the mortgage period should remain constant. Where part of the payment is being met by the mortgage support loan then, although the capital outstanding at the end would be the same, the additional repayment of the loan must be taken into account and the question is whether it has been offset by the reduction in the actual interest payments made by the claimant.

The measure for this will be the equity in the home, after the remaining loans, both the mortgage and the SMI loan, have been cleared.

Estimating, or guessing, this value in advance is an interesting, if pointless, effort. The herd of elephants in the room is house price inflation, or deflation. Added to which are all the other factors which affect house prices. Mortgage rates and SMI rates will additionally affect these estimates.

Figure 1 and figure 2 both assume zero house price inflation. If we consider that prices, in cash terms, may rise over the next 25 years at the same rate as in the past then both these figures look very different.

Figure 3

Figure 3 shows the result of the situation in figure 1 when average house price inflation of 6.4% per annum has been applied.

Figure 4 shows the result of the position, previously shown in figure 2, of the higher payments being made.

Figure 4

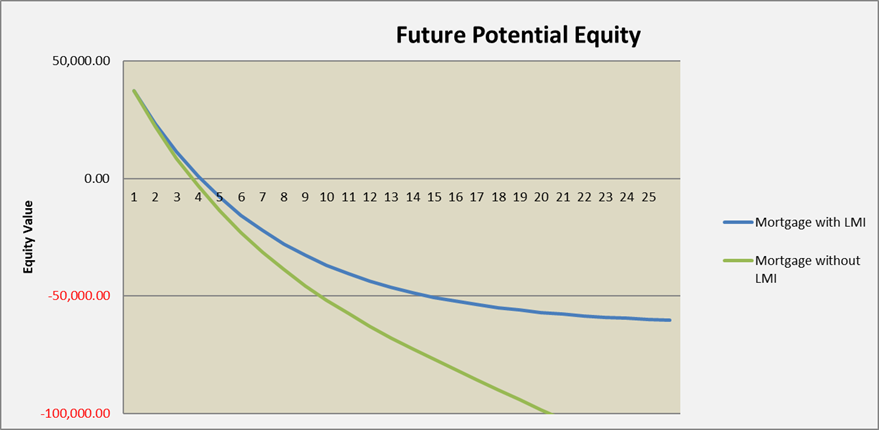

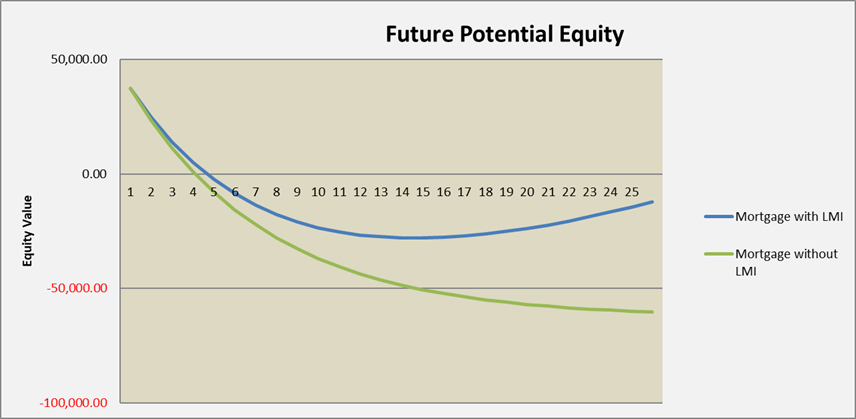

Figure 5 and figure 6 shows the results if house price deflation, at the worst level over the last 25 years were to be applied annually for the next 25 years.

Figure 5

Figure 6

There is a difference in the way in which calculation may work. The mortgage begins from the premise that the interest payable monthly is based upon the mortgage capital outstanding and where the interest payments are met in full, the capital outstanding remains constant. The mortgage support loan however has a repayable element which grows monthly as the contribution to the lender is made but also grows monthly as the interest previously applied is rolled up and becomes subject to further interest as the total of loan contributions increases.

Interest rate assumed for payments to lenders

The amount paid to the lender , which will be repayable in due course, is tied to the Bank of England’s published average mortgage rate and is called the standard rate . When the average varies by 0.5% or more from the standard rate then that new average becomes the standard rate, six weeks later. For that six-week period, the standard rate me be above or below the average rate and, of course, the standard rate may vary considerably from the individual interest rate applicable to the borrowers mortgage .

Interest rate on the loan

The interest rate charged on the loan is the weighted average interest rate on conventional gilts specified in the most recent bi-annual report, published before the start of the relevant period, by the Office for Budget Responsibility The relevant periods are 1st of January to 30th June and the1st July to 31st December. The interest rate can therefore only change twice a year at the most.

Higher gilt rates, as seen in the brief administration of Liz Truss, also tend to mean higher mortgage rates, as lenders hedging methods are generally linked.

Summary

There are complex issues which emphasise the need to take proper advice, for example people who may wish to use equity release later may find that the lender doesn’t like second charges, so there may be future potential difficulties.

The effects of the change, in particular removal of the zero earnings rule, are a little positive, in the short term. Mortgages, however, are very lengthy products and no crystal ball exists.

Low earners who have been unable to access any support may be better able to avoid repossessions because of this change. A disincentive for taking up work, that may have existed for some, may cease,

There may, potentially, be lower payments, subject to the crystal ball, when the mortgage is cleared, if the interest on the loan amount over time would be less than the interest on the same amount at the mortgage rate, that would have been paid over the same period.

It seems, in crude terms, that if the loan rate is lower than the mortgage rate then a loan is better if full payment of mortgage interest isn’t possible. This is likely to apply to many facing increasing mortgage rates pressure. Here, loans can, in probability, at least postpone difficulties until much later.

[1] https://www.parliament.uk/globalassets/documents/impact-assessments/IA15-006D.pdf

[2] https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukia/2017/117/pdfs/ukia_20170117_en.pdf

[3]https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/712109/ad-hoc-statistics-release-conversion-of-support-for-mortgage-interest.pdf

[4] https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/SN06618/SN06618.pdf

[5]https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/634132/public-attitudes-towards-taking-up-support-for-mortgage-interest-as-a-loan-rr-941.pdf

[6]https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1063673/support-for-mortgage-interest-loans-take-up.pdf

Leave a Reply