Cost of living, pensions and some difficulties

by Gareth Morgan on August 9, 2022

There’s been some discussion recently about the use of pension savings, after the age of 55, to help meet the cost of living increases that are affecting many people. You can see some of this discussion on Henry Tappers blog about pensions (a highly recommended read): The cost of living crisis – and the value of small pots | AgeWage: Making your money work as hard as you do (henrytapper.com) and following, where I’ve added some comments.

There are a few issues which deserve some further consideration here and I’ll touch specifically on two of them :

- The effect of inflation and the double hit on pensioners; why it can make them worse off in absolute cash terms

- Deprivation rules on using pension savings

Inflation and the inverse benefits problem

Inflation is bad news for those on benefits, as it always has been. Although there are, at least semi-automatic, ways in which benefit rates increase to take account of inflation, there is always a substantial lag. There is no retrospective way to help people who have faced the impact of higher costs to be met from un-indexed benefit payments. Any increase is always after the fact.

Pensioners can face a second problem caused by inflation. Notional income from pension savings. Where pensioners have untaken savings in their pension pots then this will generate a notional income. That reduces Pension Credit and, other benefits including Housing Benefit and Council Tax Reduction. This will apply particularly to pensioners who are drawing down their savings, regularly or irregularly, during retirement. Those with annuities or, typically, in Direct Benefit schemes are not affected by this rule.

The amount of notional income is calculated using the GAD tables. These tables produced by the Government Actuaries Department provide an annual notional income per £1000, determined by age and by the 15 year gilt yield. …and there’s the problem.

Gilts are government bonds and they are particularly sensitive to interest rate changes. They are issued by the UK government and they pay a fixed interest, or coupon, rate at fixed periods. When issued they tend to start at the current market interest rate. Gilt prices go up when interest rates fall, and go down when base interest rate goes up. So gilt yields rise and fall with interest rates.

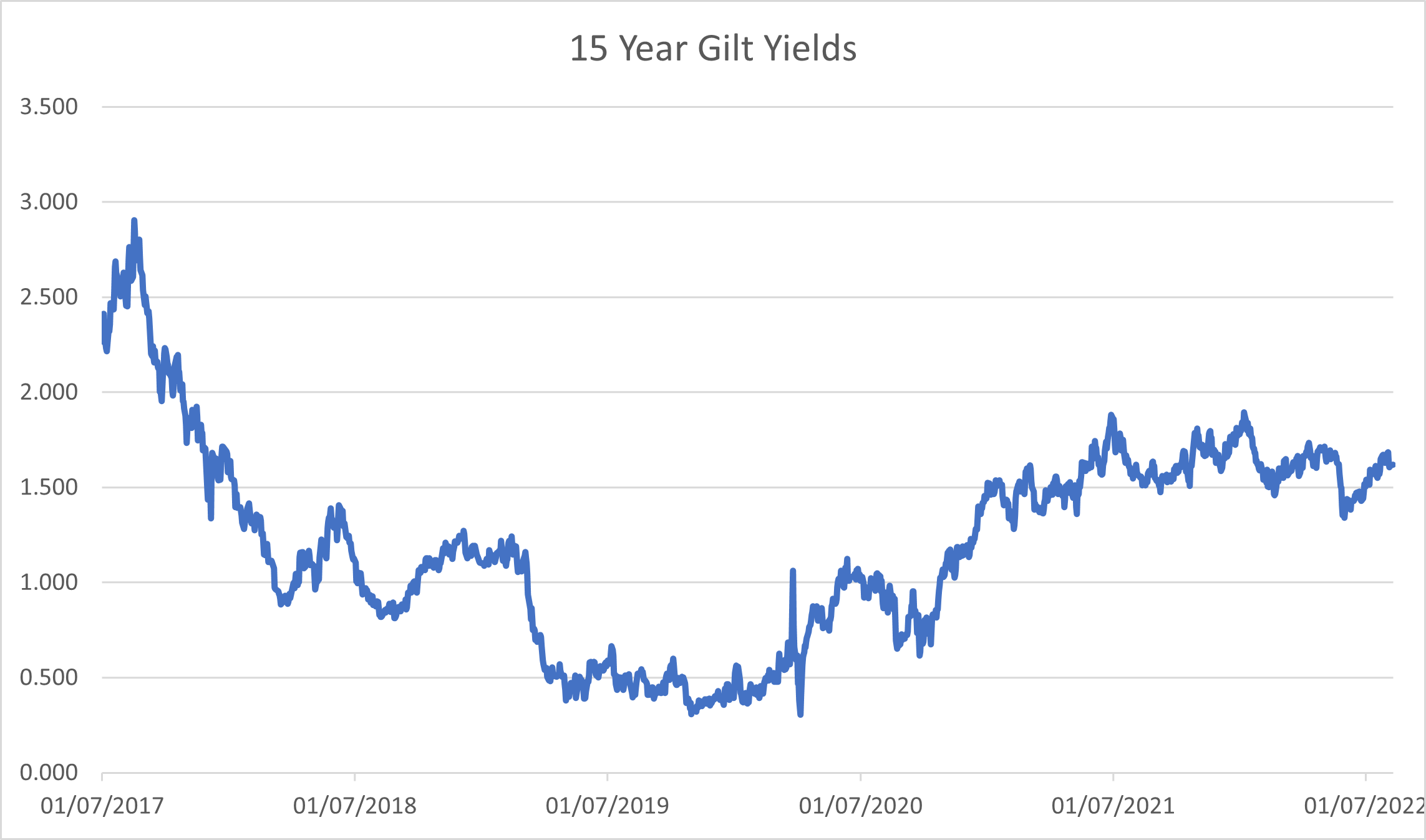

As gilt yields rise, when prices fall, then the GAD table reflects that in an increased notional return. Here, in Chart 1, you can see the change over the last 5 years in the yields, since the GAD table was last changed.

While it looks a little fuzzy, because of frequent daily small changes, it shows that the rate changes frequently and substantially. Over the 5 years, the lowest rate is 0.304% and the highest is 2.906%. There’s some rounding applied when working out notional incomes but the variation in rates does create noticeable differences in value.

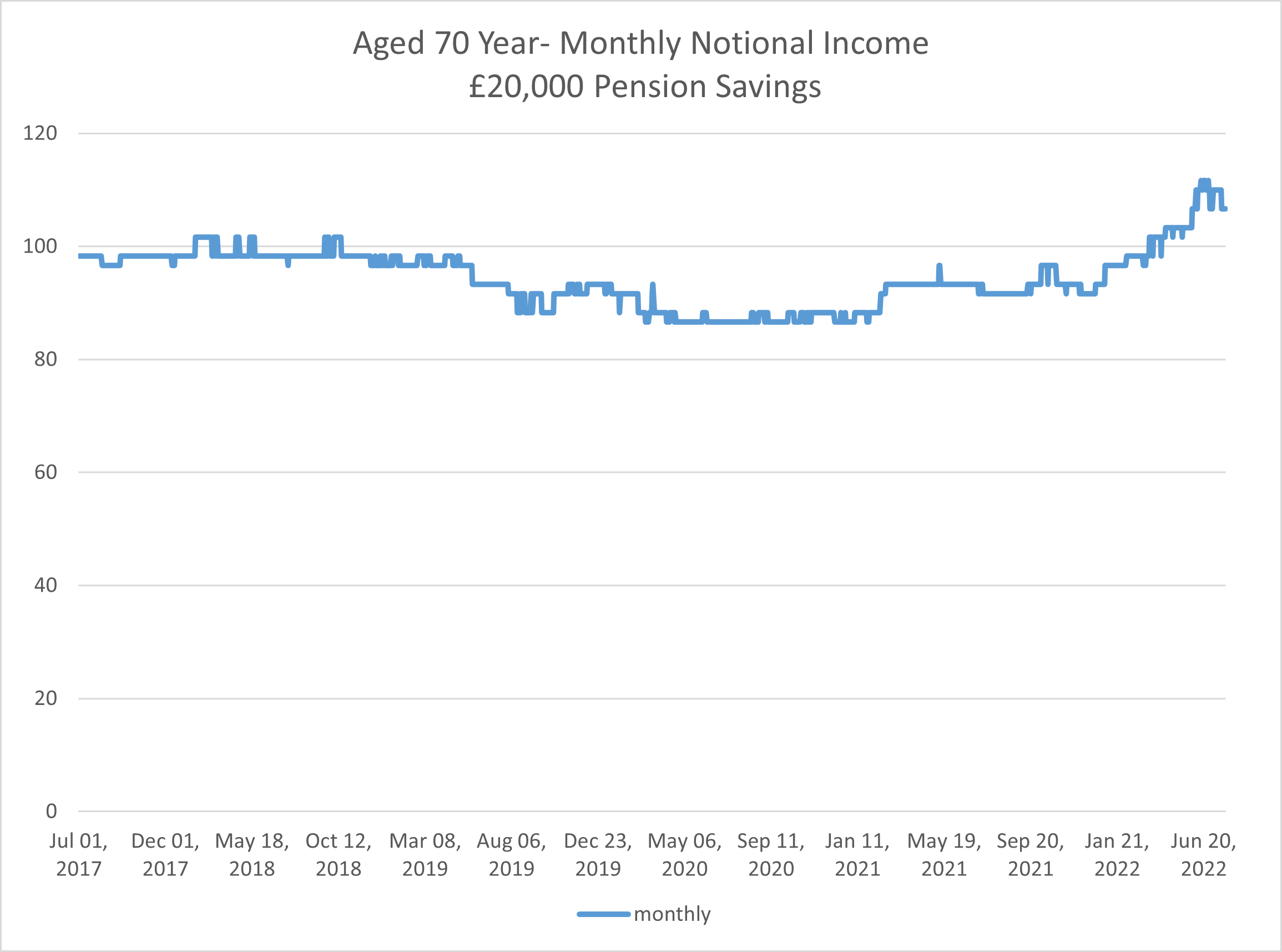

Here in Chart 2, is the resultant notional income over the same period for a 70 year old with £20,000 of untaken savings.

The maximum notional income over the period was £116.67 while the minimum was £86.67; that’s a variation of 29%. At the time of writing, we’re close to the highest end.

The effect, in benefit entitlement, of the variation is simple – at the lowest yield rate benefit would be £30 a month higher than it would be the highest yield rate.

Boiling it down, people face a rather contrarian result that as inflation rises their benefit is likely to fall. As inflation rises steeply, so will their benefit fall steeply.

There is a quirk in the system which can mean taking some money from savings and hanging onto it can be worthwhile. You can hold up to £10,000 without affecting benefits entitlement. Take £9,999 from pension savings by drawdown and that doesn’t alter any benefits entitlement. It does reduce your savings, reduce notional income and thus increase benefits entitlement. On today’s Gilt rates that would increase monthly Pension Credit by £53.33.

Deprivation

Moving onto deprivation, the DWP have commented that people should be cautious about taking money from their pension savings to meet immediate needs as they might fall foul of rules concerning ‘deprivation’.

It might be useful to have a bit of detail about how deprivation rules work. They’re designed to stop people disposing of money that they might otherwise use to maintain themselves, and then turning to the state for support instead. They kick in when the disposal either creates an entitlement to benefit or increases the amount of entitlement. They’ve been around for a long time and for eminently sensible reasons.

If you win the lottery this week, give it all to the kids and then claim benefit to enable you to eat and clothe yourself, it’ seems reasonable to say that’s unfair. The consequence of having been found to have deprived yourself is to be treated, in the benefit assessment, as if you still have the money. There is a complex set of rules that diminishes that amount over time so that you can become entitled to the benefit again in due course.

To be treated as having deprived yourself, the intention to qualify for benefit has to be there. If you don’t know that will be the effect, then you can’t have got rid of the cash in order to qualify. It doesn’t have to be the sole reason you got rid of the cash but it does have to be a ‘significant operative purpose’. The messages in Henry Tapper’s blog on spending to qualify would almost certainly be a strong pointer to this.

Whether taking pension savings and spending them, on daily living costs or meeting a financial crisis, raises some points. Where there is a balance of reasons for the spend, then the DWP and any appeals process, should consider that balance. Typically giving money to the kids, or blowing it on a world cruise, would be considered to be spending money that you could reasonably have spent on day to day expenses, and hence deprivation. Paying off a debt that would otherwise have lost you your home wouldn’t. Moving the money into a different form, such as buying an asset, isn’t normally deprivation as you still have the value.

Taking pension savings before pension age is, in itself, an interesting technical point. The value of pension savings is ignored, for benefit purposes, before pension age. It only counts when it appears in your possession as capital or income. If the money never passes through your hands, there is an argument that it can never count, but that has failed in the past. If the money taken as capital, never means that you have more than £6,000 at any time then it’s ignored for benefit purposes. Taking a series of sums and spending them so that your capital remains below that level at all times is safe in those terms.

Whether you can spend pension savings before pension age and then get Pension Credit or more Pension Credit is a test that has not, as far as I’m aware having searched Ferret’s Social Security Law Electronic Database, been tested and determined. Local authorities do look back, often over many years, to operate a similar test when assessing social care charging rules but those don’t create a precedent. Can you, perhaps many years earlier, at a time when there is no entitlement to Pension Credit, spend money, which is not at the time relevant to any benefits entitlement, be depriving yourself? There would be great difficulties in proving that, normally. If the main reason why you did that was to meet real and immediate needs, I would be very surprised if the rule applied.

If you’re already over pension age, the the same rule can apply, but there is an immediate possible entitlement to consider. Again, taking the money and giving it away, knowing that it would affect benefit, is likely to be deprivation. Spending it on real needs is unlikely to count, even if you realise that it will have that effect.

Conclusion

We know that we are all facing increases in costs and consequently inflation. For some people that will be annoying; for others it is disastrous. Helping people to find ways to deal with or mitigate their situation is crucial, especially if, as seems likely, the next administration is determined to avoid handouts or to remove resources from the areas most in need. While making use of pension savings will not be the best for the long term, it may be better than, as has been suggested by a former pensions minister, maxing out their credit cards.

Understanding the consequences, and potential costs, is part of, as always, making an informed decision. This is not easy in this difficult area and it’s not helped by the, sometimes contrarian and always complex rules which apply.

Comments

Great blog Gareth.

The thrust of any guidance to those with small pots and a pension credit entitlement is to spend the pots on household goods and do not hoard. Surprisingly similar to the thrust of the Australian Retirement Income Covenant. “You can’t take it with you when you go” v “Fear of Running out (FOR0)”- it’s the old dilemma with the twist that you need to make it to 67 in the first place.

Pensions are “precious” but sometimes they can be dangerous. The guidance on these issues needs to be spot on. I worry how many have access to Ferret’s calculators (or similar).

I am encouraging insurers and master trusts to have a strategy for the cost of living crisis. Surprisingly, even the more ESG orientated, haven’t thought about the social consequences of pensions on their own customers!

[…] Originally published by Gareth Morgan on August 9, 2022 here. […]