Spend less or earn more – Government Policy.

by Gareth Morgan on October 4, 2022

People know that when their bills arrive, they can either cut their consumption or they can get a higher salary, higher wages, go out there and get that new job

– Jake Berry MP. Conservative Party Chairman

The ‘fiscal event‘, and its reactions and consequences, are not what I really want to look at in detail in this piece. There are plenty of people, much more capable than me, commenting on the overall impact that can be expected from that. I do want to look at the very clearly expressed views of Jake Berry, that getting better pay is the answer and is the intention behind much of this government’s new strategies.

I will use the changes that were announced in the mini-budget in my calculations, to see how much difference they might make in helping people, either by improving their current situation or by affecting the way their changes in earnings will improve their circumstances.

I’m going to take an entirely artificial case of a couple, with one person working who earns £25,000 a year, with two children, paying rent of £200 a week, and Council tax of £1500 a year. (Oxford comma is deliberate). There are no disabilities or other relevant elements.

The current situation, in early October 2022, is not untypical, The tax rate is still 20% and their NI includes the levy of 1.25%, meaning the applicable rates is 13.25%.

Using weekly figures and ignoring any pension contributions (although I touch briefly on those, as a separate issue, at the end of this piece) we can see what the current situation is.

The gross earnings of £479.45 a week, are reduced by tax of £47.68 and NI of £31.59, giving net earnings of £400.18.

That will be supplemented by £268.24 Universal Credit and , in this case using the default scheme for England, zero entitlement to Council Tax Reduction. Council Tax Reduction (or rate rebate in Northern Ireland) will depend upon which nation and local authority the claimant is living in.

That gives this family a weekly income of £668.42, plus Child Benefit.

Tax cuts

To touch on the specifics of the mini budget, the government would like us to see the removal of the NI levy, and the 1p reduction in the basic tax rate, as demonstrating their commitment to helping the lowest paid to increase their real income. As always, the presentation of such changes is, at the least, selective and partial. Looking at the reality shows these changes to be very far from a giveaway.

Looking first at the NI levy, we have the removal of the 1.25%, which was intended to help meet the additional costs of the (last/this) governments’ social care charging protections, due to be introduced over the next couple of years. In the short term this was also to be used to help meet additional costs for the NHS. It’s yet to be made clear where that funding now comes from, or whether it does.

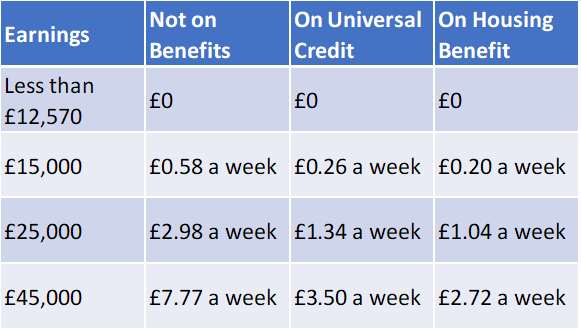

Nonetheless it will be a reduction in contributions paid for many people. What it is not, is a progressive measure; quite the reverse. Table 1 shows the effect on net earnings of the removal of the levy.

For the lowest earners, with pay below the tax and NI threshold of £12,570, there will be no gain as they pay no tax or NI in any event. For those earning above that figure then the NI that they pay will be reduced by 1.25%. The more you earn, the bigger the reduction. At £15,000 a year, the gain is 58p a week while at £45,000 it becomes £7.77.

These figures, for low earners especially, are not life-changing but it becomes worse.

Low earners are, of course, much more likely to have their earnings topped up by means tested in-work benefits. These benefits are calculated using net earnings as part of their income assessment. Tax, NI and pension contributions are deducted from gross earnings to arrive at that figure. The effect of any reduction in tax or NI contributions is to increase the net earnings figure and, consequently, means tested benefits will be reduced.

A £1 increase in net earnings will see Universal Credit entitlement reduced by 55p and, for those on legacy housing benefit, the equivalent reduction is 65p. Council Tax Reduction is most commonly reduced by 20p for each £1 although this is very variable, particularly in English local authorities.

Columns 2 and 3 show the effect on net income of the reduction in benefits after any benefit reduction is also applied. Again, for the lowest earners below the threshold figures there is no effect. For others, any income gain from the reduction in NI is substantially reduced.

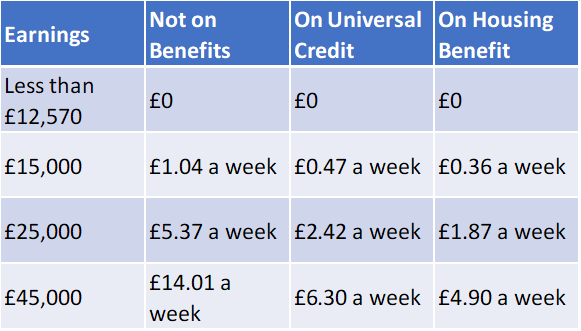

The same effect is seen when the tax rate is reduced. Table 2 shows the combined cuts of NI and the 1p reduction in the basic tax rate, together with the very different final effect for those receiving in-work benefits.

Again, the very much lower initial gains for low earners, compared to those earning more, are made even smaller by the reductions in means tested benefits.

It’s clear that the few pence a week gained by low earners will not go far to meet the energy and other inflationary pressures facing people this winter. For the family that we are considering, the £2.42 a week increase in their incomes, is an increase of 0.36%.

Earning more

What about following Jake Berry’s advice and increasing their earnings? Inflation in September seems likely to be about 10% so what happens if they’re fortunate enough to get a new job, or negotiate a pay increase of 10% on their previous earnings.

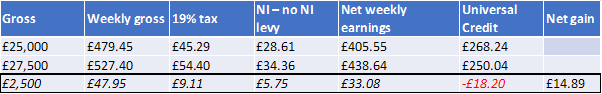

In this comparison, the tax rate used is 19% and employees’ NI is the post levy rate of 12%.

Using weekly figures, shown in table 3, their gross pay increases by almost £50 but their net gain is much smaller.

Even after the reductions, their tax and NI reduces the gross increase by almost £15 and the remaining £33 has the 55% Universal Credit taper reduction applied to it of over £18. That leaves them with a real income increase of less than £15.

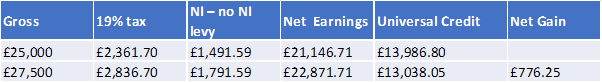

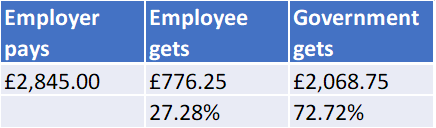

Annually, as table 4 shows, their extra earnings of £2,500 become a real increase of £776.25; a marginal deduction rate of 69%. Far higher than the 45% higher tax rate which disincentivizes higher earners.

It’s interesting to see who gains from their, strongly politically encouraged, drive to earn more. There is one other element to add to find that out. As well as paying £2500 more to the employee, the employer also has to pay an employers NI contribution. This has also had the NI levy removed from it so reverts, currently, to the previous 13.8%. This means that, as well as paying £2,500 extra to the employee, before deductions, they must also pay increased employers’ NI of £345.

Taking that into account, table 5 shows that doing what Mr Berry says, and earning more by working harder means that, in this case, almost three quarters of what you earn will go straight back to the government. It hardly seems in line with the low tax philosophy of the new administration but, after all, we are not talking about bankers and hedge fund managers.

Pension savings

While not directly linked to the main issues here, there is a very concerning trend becoming apparent of, particularly low paid, employees pausing or ceasing contributions into their pension schemes.

The Chartered Institute of Payroll Professionals (CIPP) surveyed employers last month and found 35% of them were seeing an increase in employees pausing contributions to workplace pensions. Of these, about two thirds gave the increased cost of living as the reason for stopping payments into the scheme. When contributions are paused, that means that they will restart at the next re-enrolment point unless opted out for a further three years. Where this happens, it is also likely that the employers contribution into the pension will also stop.

Understandably, for some people, these pension contributions may seem to be relevant only to the distant future and immediate financial problems will weigh much more heavily. The extra money to meet immediate needs may look extremely tempting.

What isn’t commonly realised is that there may be another very real hit to incomes that will happen if contributions are paused or stopped. Net earnings, as used in assessing means tested benefits, also take account of pension contributions. More generously than in some legacy benefits, Universal Credit disregards the whole of pension contributions when it calculates net earnings. That means that paying £50 a month into a pension scheme will reduce the income used in calculating UC by £50 a month. Lower-income means higher benefits and, for £50, the application of the UC taper means that the benefit will increase, in the following month, by £27.50. Conversely, stopping pension contributions of £50 a month will reduce the amount of UC by £27.50 in the following month.

That means that it is all too easy for somebody to think that by stopping a £50 payment they will be £50 better off, and better able to meet bills. The reality is that their real increase in spending power will be £22.50 while the loss in pension savings may very well be substantially greater.

This does not seem to be being made clear, by anybody, when people are making this decision.

Similar effects are seen when increasing pension contributions in legacy benefits. Tax credit goes up by £20.50 and Housing Benefit goes up by £16.25. The same amount reduces when contributions cease.

As this appears to be an increasing problem it is vital that people understand the effects of this kind of decision fully before they take such a potentially unwise decision.

Conclusion

This is being written while the Conservative party conference is taking place in Birmingham. It is being heavily trailed that working age benefits will not be uprated in line with inflation. Instead we are being told that the government’s tax cutting measures will help the low paid and that they should seek better paid jobs if they want to have more money to spend.

The figures, in this example, seem to show, once again, the fallacies and flaws (to be generous) in these arguments.

Gareth Morgan

4th October 2022

There are a number of reckoners which we produce, including comparisons of gains and losses with different earnings, while receiving or not receiving benefits and showing the benefits value of pension contributions. You can find these, and many others, at Ferret Reckoners – Home (webreckoners.com). Most are free.

Leave a Reply