Inflation increases for earnings and benefits – it’s not that simple

by Gareth Morgan on October 6, 2022

The driver for limiting benefits increases, instead of linking them to inflation, appears to be presented as an argument that it’s not fair for working people to receive a 5% pay increase while people on benefits will get around 10%. That seems to be a very simple and easy comparison to make and might appear to have some justification.

As always seems to be the case with benefits, that’s not the reality. It would be nice to believe that those presenting this argument are merely ignorant of the way the tax and benefit system works but, if so, they are remarkably resistant to accepting any corrections of their errors.

As an example, I’ll use the fictional but very standard, family that I used in my earlier blog post this week looking at tax and NI cuts and the effects of pay increases. Spend less or earn more – Government Policy. – Benefits in the Future.

I’m going to take an entirely artificial case of a couple, with one person working who earns £25,000 a year, with two children, paying a social rent of £200 a week, and Council tax of £1500 a year. (Oxford comma is deliberate). There are no disabilities or other relevant elements.

How would they fare in the two indexation scenarios? How much difference will there be?

The first, obvious, point is that in neither scenario is their income likely to increase by either 5% or 10%. Their income is, like very many average, or below-average, earnings families made up of a mix of income types.

In order to attempt to assess the alternative effects of the presented options we’ll need to go through a number of separate steps. I’m going to assume that the earnings rate of increase will be limited to 5% and then consider the two different potential rates of benefit increase.

A 5% increase in gross earnings, next year, will not translate into a 5% increase in net earnings. The effect of the, frozen, threshold figures for tax and NI as well as the 1p drop in the basic rate of income tax will see to that. I have not applied the current, for this month, additional 1.25% NI levy in the comparison, for current earnings, as that now seems to be just a ‘blip‘.

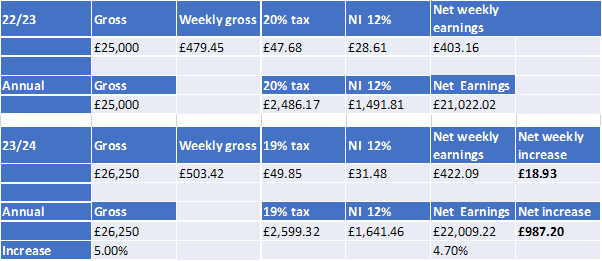

Table 1

The 5% increase in gross earnings becomes 4.7% increase in net earnings, after taking into account the cut in the tax rate. For that, blame the frozen threshold figures which mean that the lower rate of tax, plus NI, is payable on just over 10% more earnings. The previous tax and NI-able figure of £12,430 has become £13,680.

The increased net earnings will have an effect on the benefit entitlement, reducing it by the Universal Credit taper.

Our next step is to assess the benefit increase, from any indexation. The amount of Universal Credit currently being received is not the amount to which any factor is applied. The amount of Universal Credit in payment has already been reduced from the maximum, in the current year, because of the family’s income.

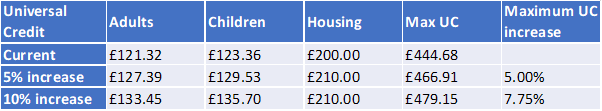

The maximum amount of Universal Credit for our artificial family, in 22/23, is made up of a number of separate elements which are added together. In this, very straightforward, example, the elements (converted from monthly to weekly) are an allowance for adults of £121.32, an allowance for the children of £123.36 and a housing amount for their rent of £200. The maximum Universal Credit figure is £444.68 but it has been reduced because of their level of income.

Whatever the increase factor applied, it will not be assessed across the whole of the maximum amount of Universal Credit. The housing element, currently £200 will be set at the current rent amount in force, for social tenants, assuming that the bedroom tax does not apply to reduce it.

Social rent increases are regulated by the government and this has been set in recent years at CPI +1%. Because of the possibility that this would mean an increase of 11% on rents in the next year, the government are currently consulting on introducing a cap of either 3%, 5% or 7% instead. For the purposes of this example, I will use 5% as the figure in all of the assessments.

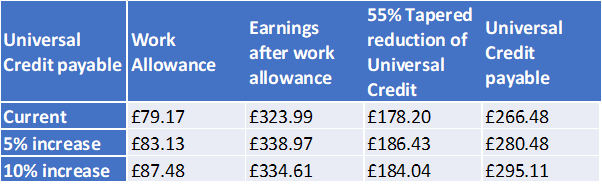

As a means tested benefit, Universal Credit is reduced by income, including earnings but not all earnings are used. In this case, as a family with children, some of the net earnings, called a work allowance, will be ignored and the remainder will be subject to a 55% Universal Credit tariff reduction. Work allowances were raised substantially in November 2021 and increased by indexation in the current year. I’m assuming a level of indexation which matches the other benefits increases and it should be noted that the lower the increase percentage, the more earnings will be used in the tapering process.

Table 2

Table 2 shows that, for this case, a 10% increase in ‘benefits’ is actually a much smaller increase in the maximum Universal Credit, because our families rent increase is likely to be smaller.

Our next step is to determine how much the maximum Universal Credit has to be reduced because of the level of earnings in this case.

Table 3

In this example, a 5% benefit uprating will produce a 5.25% increase in Universal Credit payable. Uprate the benefit by 10% and the increase becomes 10.74%.

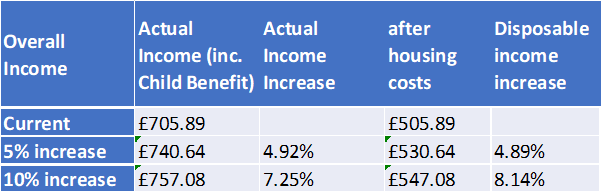

That is not the figure which matters most to this family. For them, the bottom-line income from all sources, after paying their rent, is likely to be what matters.

Table 4

The child benefit has also increased from the current £36.25 a week to £38.06 at a 5% increase and £39.88 where 10% is applied. Their total income increase is shown in table 4 and the disposable income, after meeting their rent increase, gives us the final figure for them.

A consistent 5% increase in earnings, benefits and rent will give them a 4.89% increase in disposable income. Increase the benefit rate to 10% and the disposable income increase becomes 8.14%.

With inflation of 10%, neither of these options will leave them better off. As shown in my previous blog post, the 1p cut in the basic tax rate does very, very little to help here.

This may seem to have been an overlong and complicated way to arrive at a not-very-different outcome but it matters. It matters because this is only an example. If the example had been different, with a different family type, earnings or housing costs, then the results could have been very different. A simplistic view that only the percentage benefit uprating matters will not reveal the impact on different families. It’s also important to remember that, without uprating the stealth taxes within the benefit system, including the overall benefits cap, local housing allowances and others, that any crude increase in benefit entitlement can only push more people into those even more complex and damaging assessments.

Gareth Morgan

October 6th 2022

Comments

[…] Inflation increases for earnings and benefits – it’s not that simple […]

Hi I was hoping you could advise me. I understand working age benefits could be reduced by less than CPI but disability benefits such as PIP must increase with inflation by law.

My question is, how is the SDP and EDP treated? Is the increase of these protected by law like PIP or can they be increased less like working age benefits?

I know they’re paid as part of a working age award but when we had that 4 year benefit freeze the premiums still increased so that made me think (or hope) that disability premiums had to increase by CPI in law

Also on a seperate subject do you know what the plans are for the LHA rates? I know during lockdown they said frozen until 2024/25 but surely with CPI at 10% and mortgages at 6% they will have to look at that again

Thanks in advance for your help

Premiums aren’t formally linked to any inflation measure but they have historically been increased when other elements have not. As for LHA, and other, rates. While we might think that they should be increased, past experience does not bode well, at a time when the government is looking for savings.