Universal Credit & Rent – Landlords, be cautious about being helpful

by Gareth Morgan on February 16, 2020

(Charts and tables amended 18/2/2020 to correct misalignment and 23/2/20 to simplify UC Calculation)

The House of Lords Economic Affairs Committee has launched an enquiry into the economics of Universal Credit. It’s calling for written contributions to be submitted by February 29th. Whatever your views on the House of Lords as a second chamber, its members include some very sharp, experienced, and expert people. That means that their enquiries tend to be thorough and perceptive.

The Committee is looking at whether Universal Credit is meeting its original objectives and whether the policy assumptions reflected in its design are appropriate for different groups of claimants. It will also examine the extent to which Universal Credit meets the needs of claimants in today’s labour market and changing world of work.

It’s looking at collecting a wide range of diverse views and I’ll add my voice to those encouraging people to submit evidence[i]

there is a list of questions that the committee is asking, but the ones that particularly interest me are

- How well has Universal Credit met its original objectives?

- Does Universal Credit’s design adequately reflect the reality of low-paid work?

- If Universal Credit does not adequately reflect the lived experiences of low-paid workers, how should it be reformed?

I’m going to submit evidence on a few areas including technology, simplicity, and in-work support.

One of those areas, that I’ve written about before, combines all three areas and I thought that I might expand a little here on the rather concise requirements that the committee has for evidence.

Universal Credit is a single system supporting those in and out of work. Hence, as people’s earnings increase or decrease, their Universal Credit amount will adjust smoothly to reflect this

Universal Credit: welfare that works. – DWP White Paper 2010

I wanted to look more closely at what people are left with, from their net earnings, after paying rent. What I found seems to show, for some people, that landlords who try to help their tenants to budget, may be making things more difficult rather than easier.

Means-tested benefits often work poorly when people circumstances change. The reassessment of entitlement depends upon timely notification of the change, speedy and accurate recalculation of entitlement, and efficient implementation of the new level of benefit. That puts the responsibility, firstly on the claimant who, depending upon the type of change, may have other priorities and afterwards on an administration which has traditionally underestimated the frequency and severity of changes of circumstance.

Benefit systems have been designed by people who, in the main, have more stable lives and incomes than many benefit claimants. People form and break relationships, gain and lose work, move accommodation, have incapacitating accidents and lead frequently chaotic lives.

Building a system that reduces the responsibility of people to inform the state about changes in their lives can help. If that system can efficiently, and quickly, reflect those changes in the level of benefits paid to families, then that would clearly help to meet the changes in need caused by the changes in circumstance.

This is clearly a win for Universal Credit…. or would have been if it had been achieved. Universal Credit’s response to such changes assumes that every change applies for the whole of the month-long assessment period, before Universal Credit is paid a week later. That means that whether the change actually happened on the first day, or last day, of the month, it will have no effect on the amount of UC paid in the following month.

Still, at least those people who don’t have changes in circumstance in that month, who get the same pay every payday, who pay the same rent every rent day will be able to rely on getting the same benefit every benefit day.

That’s obvious, surely?

Sadly, very little is obvious with Universal Credit, and this is a classic example.

Let’s take the case of a couple who both work on the 2019/20 National Minimum Wage level of £8.21 an hour. One works for 35 hours a week, paid monthly, and the other works for 10 hours a week paid weekly. They have two children and pay rent to a social landlord of £150 a week.

The full-time worker is paid £1116.31 a month net and the part-time worker earns £355.77 a month net. Their rent works out to £650 a month. On the basis of those figures, they would be entitled to £907.70 Universal Credit every month.

That will leave them with £1,779.78 after paying their rent. Having consistent income and outgoings makes their budgeting and planning much easier.

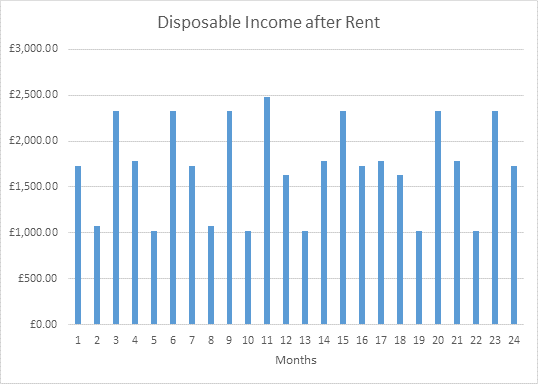

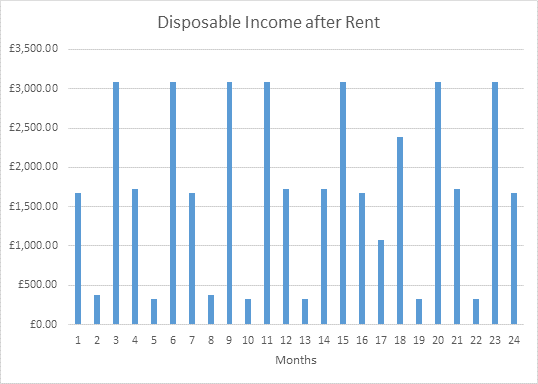

Or it would do if they had consistent income. Figure 1 below shows what their actual disposable income after rent will be month by month for the next two years.

Figure 1

There is a variation in the disposable income, that they have left each month, of up to £1,458.27.

In some months they will have £2,483.05 left after paying their rent while, in other months, it could be as low as £1,024.78. Universal Credit has taken a family with steady consistent work and earnings and imposed what looks like a set of random variations upon them

It isn’t random though, it is a deliberate result of the design of Universal Credit, however hard that should be to believe.

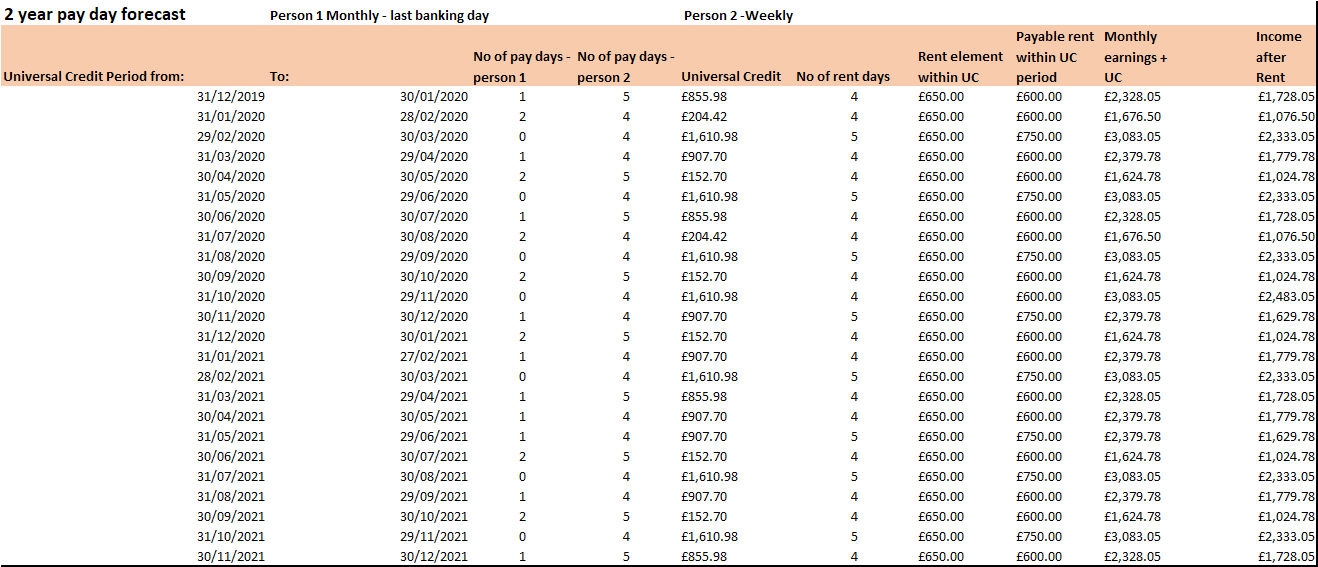

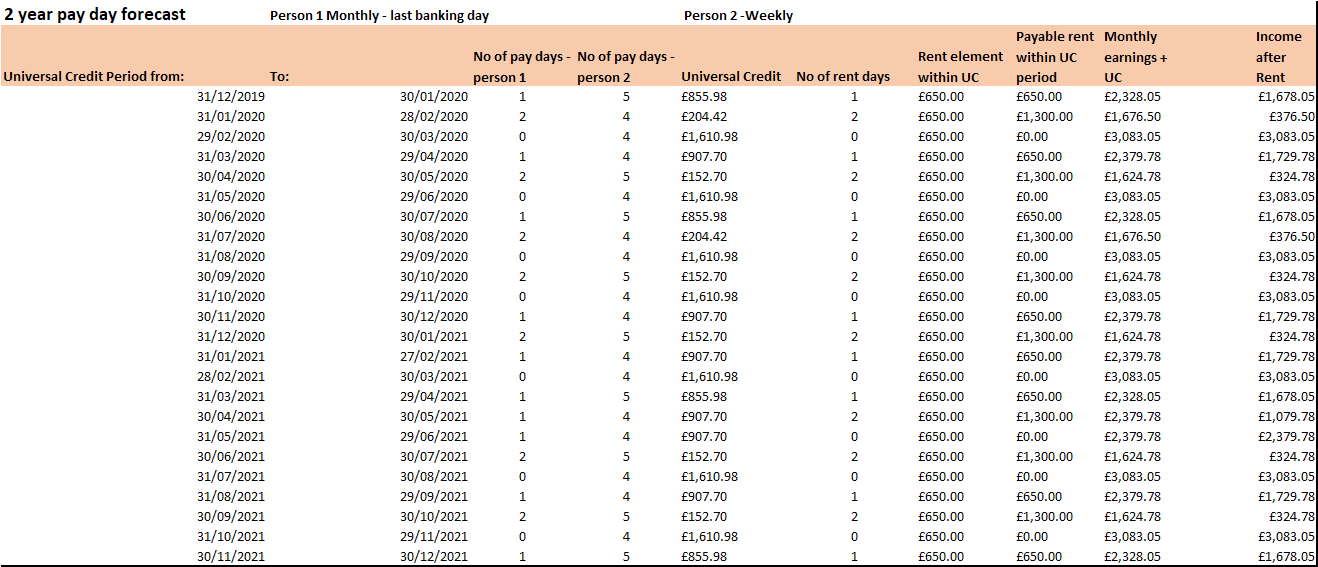

Table 1 below shows why this happens

Table 1

I said earlier that Universal Credit looks at what happens during the previous month when calculating the following months entitlement. That means that it looks at the earnings and income that people have during that month. To be exact it looks at how much people are paid, on days that fall within the Universal Credit assessment period.

The table shows the pattern of Universal Credit assessment periods, which are based upon the date that the benefit is claimed. In this example Universal Credit is claimed on the last day of 2019. The rest of the table shows what happens during each of those assessment periods.

The two people working are paid at different periods. One is paid weekly and the other paid monthly, on the last working day of the month.

Neither of these are uncommon, the last working day of the month is the most popular pay day for monthly paid people with 38.6% of earnings paid on that day. 24.6% of employers pay people weekly, commonly on Friday. (CIPP Payslip Statistics Comparison 2008 – 2016).

The consequence of that is that, for each member of this couple, there may be different numbers of paydays in each Universal Credit period. That means that there will be different amounts of earnings used in the Universal Credit calculation in that month. For the person paid monthly, there may be one, two or no paydays included while for the weekly paid person it will either be four or five.

As you can see from the table, in some months there will be no monthly pay for person 1 and four weekly pays of the much lower amount for person 2, while in others there may be two monthly paydays and five weekly paydays used in the assessment. That means that Universal Credit is being calculated sometimes on monthly net earnings of £328.40 and sometimes on £2,643.12. Because of that the Universal Credit entitlement can range from £1039.80 a month to nothing.

Where there is no entitlement to Universal Credit in that month, that causes more problems because this family will then have to reclaim the benefit in the following month, otherwise they will just stop receiving it.

The final result becomes more complex, because from the monthly Universal Credit this family must pay their rent and, as shown in the table, in some months they will be five rent days to be paid from the Universal Credit and in some months there will be four. Universal Credit averages weekly rents over the year into monthly equivalents (less one day, see https://benefitsinthefuture.com/weekly-rent-and-universal-credit-dont-panic/ ).

This, remember, is the result of the design of the much simpler, and easy to understand, benefit replacing the complex legacy system. As the government wrote in 2013, when describing what support would be needed to help people, “It is anticipated that the demand for services will change; some will decline, (for example the extensive advisory service needed to serve the complicated network of existing benefits).

The results shown here are, to a large extent, the consequence of paydays and Universal Credit claim days in the example being close together. That again is not uncommon, many people will stop and start work at the end of a month and consequently claim benefits at that time as well. There are many people who will not have these variations in Universal Credit, particularly if all their earnings and housing costs are paid monthly and then dates of pay and Universal Credit are more widely separated.

The lack of understanding of this complex relationship between earnings, benefit, housing costs and disposable income is leading to some unfortunate consequences, caused by landlords trying to help.

The DWP have been carrying out a trial where, for those they pay rent directly to the landlord, they pay each calendar month. Previously those people who had their rent paid direct to their landlords had a month paid every four weeks, 12 times a year, with one payment skipped. This new arrangement, which aligns the rent period to the tenants Universal Credit period is expected to save social landlords thousands of hours in administrative work.

That may help, but where tenants get their housing support as part of their Universal Credit, monthly rents may have a very different effect. Social landlords are moving away from weekly rents to 4 weekly or monthly rent cycles, for administrative reasons and to align more closely to Universal Credit. Private landlords have already got a predominantly monthly rent cycle.

That will not help everybody.

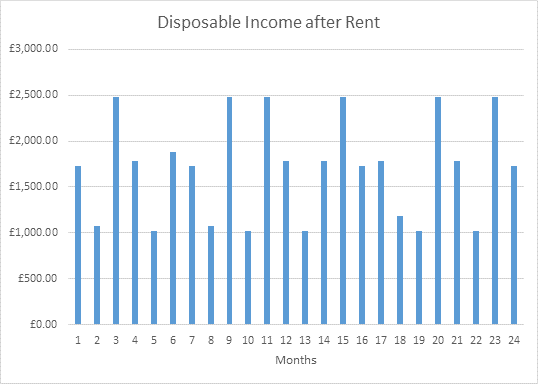

In our example if the rent moved to a four-weekly cycle, the consequences of paying £600 rent every four weeks are unhelpful.

In some months the household will still have £2,483.05 left after paying their rent, but it could, again be as low as £1,024.78, although in a different pattern. as shown in figure 2 and table 2 below.

Figure 2

Now instead of having to meet four or five weekly payments of rent from one Universal Credit payment, they will have to meet one or two four-weekly payments. That’s four or eight weekly payments.

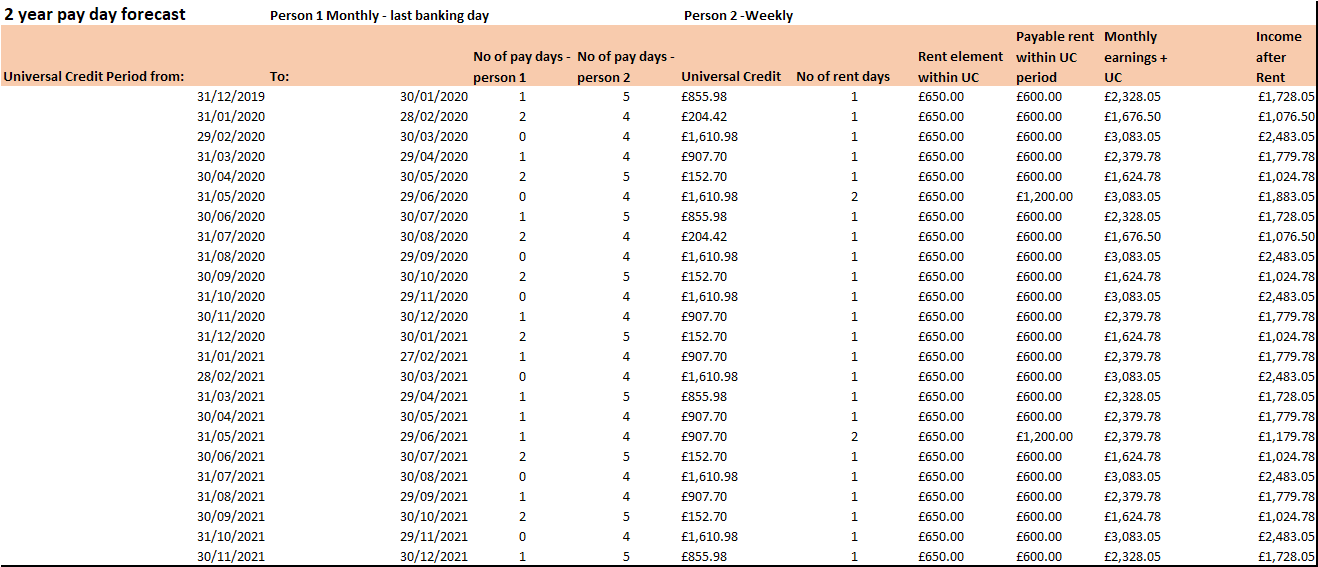

Table 2

If a landlord moved their rent collection day to a monthly cycle and chose, in this example, the last working day of the month in order to align with the most common pay cycle then the result becomes extreme.

Figure 3 and table 3 below show that in some months the household has £3,083.05 left and in other months £324.78., as they must meet two months’ rent in some assessment periods and none in others.

Figure 3

This is because Universal Credit assessment periods are based on calendar months while banking days take account of weekends and public holidays.

Table 3

These patterns therefore also change for Scotland and Northern Ireland with their different, and larger number of, public holidays. Ferret’s Benefit Period Reckoner, from which the charts and tables are taken, shows that the variation on those administrations is even greater.

Conclusion

I’ve written before about the problems that different pay cycles cause because of the rigid rules in Universal Credit about when earnings are taken into account. I expected different rent cycles to cause a similar effect, as it does. What I had not fully realised was the magnification of the effect, for a minority of people with particular rent dates close to the Universal Credit assessment period dates, that can take place.

I am worried that social landlords, in particular, may think that by moving to a rent cycle, that matches the monthly assessment of Universal Credit, they will make it easier for their tenants to budget.

For some combinations of claim and rent dates, that may be the case but, for others, as these figures show it may make budgeting even harder.

Whatever the individual circumstances, of a tenant or landlord, what is clear is that they need to understand the effects of any changes.

What is even clearer is the failure of Universal Credit to make the benefit system simpler when it can take people with steady incomes and expenditure and impose a seemingly random income on them.

One final word, the White Paper said,

as people’s earnings increase or decrease, their Universal Credit amount will adjust smoothly to reflect this”

It won’t. I have modelled less-regular earnings amounts in the same way and the results can be much much worse.

Gareth Morgan

February 2020

[i] https://www.parliament.uk/business/committees/committees-a-z/lords-select/economic-affairs-committee/news-parliament-2019/universal-credit-inquiry-call-evidence/

Comments

[…] that an element of the assessment of Universal Credit is so irrational as to be unlawful. Gareth Morgan has explained, at some length, how Universal Credit manages to take information about regular, […]