What have Debt Counsellors, Building Societies, Landlords and Energy Suppliers got in common with Payday Lenders and Catalogue Shopping?

by Gareth Morgan on November 18, 2018

What have Debt Counsellors, Building Societies, Landlords and Energy Suppliers got in common with Payday Lenders and Catalogue Shopping?

Answer? They’re all keen on regular payments by their clients and customers and that, in turn, means that they like people who budget. They’re also all likely to suffer because of a Universal Credit design decision.

Poorer people are told to budget. There seems to be at least a residual belief, amongst some people, that poor people are poor because they are feckless and reckless spenders. In fact, it is very difficult to live at benefits levels without being extremely good at budgeting. That can mean making difficult choices about priorities in each spending period, with some regular payments reduced or delayed because of more immediate needs. Nevertheless, budgeting works best with regular, predictable income and regular predictable outgoings.

Many people, at all levels of income, pay regular amounts to their energy suppliers, calculated to take account of seasonal variations in usage. Spreading the cost of larger purchases over time may be the only way for others to acquire much needed items. The government spends money, at least a little money, in supporting people to budget better and to handle their finances responsibly.

Writing about existence at benefit levels has largely looked at the difficulties of people as customers of companies and bodies that are robust enough to be able to afford delays or write-offs of debt. The willingness of these creditors to negotiate can be seen as almost a duty and there is an apparent assumption that they understand the circumstances and pressures of life and incomes of the poorest in Britain.

Characteristic of ongoing needs, and much credit, has led to almost compulsory budgeting through a pattern of regular payment. Whether these are fixed liabilities, such as mortgage or rent payments, estimates of future consumption, energy bills, or repayment of debts and arrears, there is an underlying assumption that a regular pattern of income will make these commitments workable. The consequence can be that failure to meet regular payments is seen as deliberate with other, less ‘deserving’ spending having intervened.

It is often forgotten that not all those who receive the payments have the resources themselves to be flexible and absorb delays or interruptions in payment. Buy to let landlords with monthly mortgage payments to meet from their rental income or companies with borrowing to service may have narrow limits themselves.

There is a fundamental underpinning of this pattern of budgeting; regularity and predictability. The government points to the way in which working people on monthly pay organise their finances as the model for the future benefits system, especially Universal Credit. It would be expected therefore that, for working people in the new benefits system, the design and structural results would support and reinforce this.

But it doesn’t.

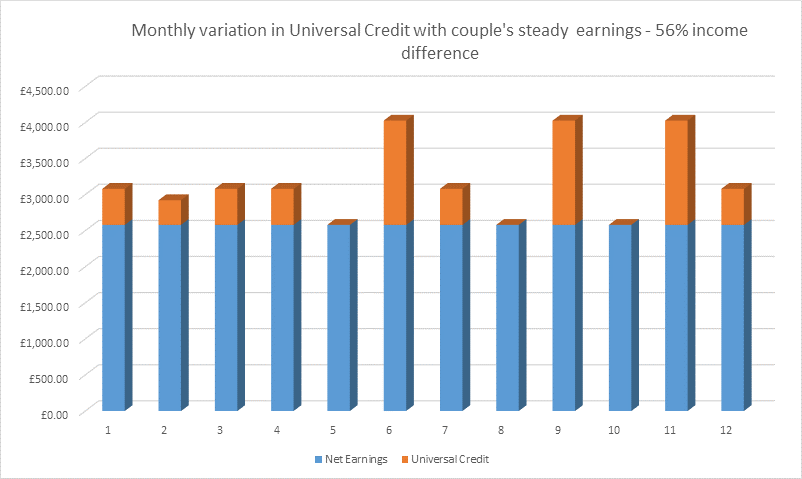

Working claimants of Universal Credit can see enormous, and hard to predict, variances in the monthly amounts of the benefit, even when they have consistent levels of earnings from their work. The disconnect between the 12 monthly payments of Universal Credit, based on the income actually received in the relevant period, and the pattern of weekly-based pay cycles, last day of the month pay-days or less regular payments cause these variations. The results are discussed and demonstrated in https://benefitsinthefuture.com/universal-credit-and-patterns-of-earning/ .

Lenders and suppliers are not generally especially experts in the benefit system. They can be presumed to believe the narrative, that the new benefits system is designed to ensure that the pattern of income will be similar to those with earnings but no means-tested benefits. This may lead to difficulties for both parties. Difficulties for their customer in meeting liabilities, because of the pattern of benefit payments, may be seen as a choice made within consistent circumstances.

Policies developed and applied on the basis of consistent incomes may fit poorly with a real inconsistency of incomes. Does awareness of this situation for individuals lead to different treatment by creditors or courts… or would awareness do that?

For some creditors, forbearance or flexibility is possible but for others, where they have their own liabilities, it will be difficult. It will be worse, though, if either party is ignorant of the situation. If there is an assumption that the failure to make full payments is deliberate, rather than a result of Universal Credit rules, then responses may be harsher and more automatic. Should there be a better awareness of the possible patterns of benefit payments?

The problems for the claimants go beyond budgeting. One of the most common regular payments people make is into their pensions. Many people do this as part of their pay while others set up regular pension savings amounts. Universal Credit doesn’t take earnings used for pension contributions into account as income in its means-test. That means that, for example, £100 paid into a pension this month will reduce the income used in the means-test by £100 in next month’s benefit. That will increase the amount of benefit paid by £63 in that month because of the tapered reduction in benefit that earnings are used for. If someone makes that payment in a period when Universal Credit treats them as not having earnings then they will lose that £63 completely. Not making that contribution in that month, but paying twice when it’s a month when earnings are taken into account, will get an extra £126 in benefit. It’s unlikely that payroll systems, direct debits or standing orders can cope with this.

As the article, linked to above, shows, it is possible to know, in advance, the pattern of payments of Universal Credit; but it takes a knowledge of each individual’s circumstances to do that. That may be impractical, and inappropriate, to do for every customer. Understanding that the situation exists, however, means that when difficulties with regular commitments become apparent, it could be possible to explore Universal Credit as a cause.

The better solution, of course, would be for the government to fix the situation of their own creating which means that the people they tell to budget are being placed, by them, in a position where they can’t do it.

Leave a Reply